“What happened to Riley Brennan?”

Chris Stuckmann’s debut Shelby Oaks poses this question ad nauseam — as does its viral marketing — a mystery about the disappearance of an amateur paranormal sleuth, whose answers end up familiar if you’ve seen any horror movie in recent years. Stuckmann’s patchwork genre piece introduces some intriguing formal and thematic ideas, but immediately discards them in favor of something more traditional. This isn’t always a setback; the novice filmmaker wears his influences on his sleeve, and proves occasionally adept at tightening the story’s screws. Unfortunately, it doesn’t quite work in the end, but if nothing else, it makes for a sincere first effort from someone who will, in all probability, make a good horror movie someday.

The partially found footage saga plays like an unofficial sequel to The Blair Witch Project, the terrifying 1999 low-budget hit that practically spawned the modern trend. Stuckmann, best known as a video film critic who began in YouTube’s infancy, massages the concept into an intriguing psychological shape. It’s the tale of an early YouTube creator, Riley Brennan (Sarah Durn), who goes missing with the crew of her low-fi ghost hunting channel Paranormal Paranoids in 2008. We’re introduced to this story not only through recovered video footage of Riley’s mysterious encounter with a figure off-screen — the last time she was seen alive — but through the Lake Mungo-like conceit of a true crime documentary recounting her disappearance, and chronicling reactions in the aftermath. These come courtesy of not only people involved with the case (Keith David in a cameo as a prison warden), but from Riley’s distraught older sister Mia (Camille Sullivan), and from conspiratorial corners of the internet, whose denizens can be seen eagerly digging and theorizing, turning the question of what happened to Riley into a worldwide trend.

It seems, for these initial twenty minutes, like Stuckmann might be crafting a film in which a content creator becomes quite literally subsumed by their hobby, and becomes content themselves, their life open to interpretation and ripe for voracious consumption. There’s even a flourish where he pulls further back, to the making of this in-world true crime doc (shot years after Riley was last seen), as one of the documentary’s cameras captures an instance of shocking violence that happens to provide Mia with clues about where her sister might be. In the modern, media-saturated landscape, the idea of a found footage movie about found footage sounds like a wonderfully mischievous formula, but this is the only time it’s ever broached. From then on, Shelby Oaks becomes a movie in the more traditional sense, albeit an amateur one whose unobtrusive staging and blocking might’ve benefitted from the lo-fi conceits of its early scenes.

Although Mia’s search involves poring over old tapes, and visiting libraries to research micro-film — Struckmann knows how to play the hits — the film quickly ceases to be about media in any meaningful sense, and uses articles and bits of footage as almost any other horror movie might, i.e. for their expository purpose. Riley’s crewmates, we quickly learn, were brutally murdered, but Riley herself went missing in the dilapidated town of Shelby Oaks, a fictional place resembling Chippewa Lake. Its amusement parks and prisons appear to have been rotting for decades, even though they’ve only been out of use for a few years. This temporal acceleration, while mentioned off-hand, proves of little consequence, but it allows Mia to go hunting for her lost sister in some creepy locales (at least one of which, the prison, forms the venue for vise-grip sequence awash in darkness).

The central drama, of Mia searching for Riley, and using demonic symbols as major clues (much to her husband’s chagrin) takes place in the appropriately named Darke County, Ohio. It sounds made up for the movie, but it’s a real place not far from where Stuckmann grew up. This domestic backdrop is never quite compelling given its lack of screentime, but there’s only so much of Shelby Oaks’ mere 102 minutes that can be devoted to Mia’s marriage given how much else transpires. New concepts and sub-genres seem to arise every handful of minutes. There are pagan symbols, satanic rituals, words scrawled on walls in blood, wooden stick figures à la the Blair Witch movies, a cabin in the woods, ghostly dogs, a creepy dungeon, shadowy figures in old photographs, a possible possession, a serial killer, a strange old lady, and even demonic specters that date back to the sisters’ childhoods, just like in another found footage landmark, Paranormal Activity. You could pick a recent horror hit out of a hat, and chances are Shelby Oaks bears some major resemblance to it. However, these homages and references rarely coalesce, and they build to a climax that struggles to live up to its intended crescendo. Its closing moments aren’t so much shocking as they are shrug-worthy, thanks to some incoherent assembly.

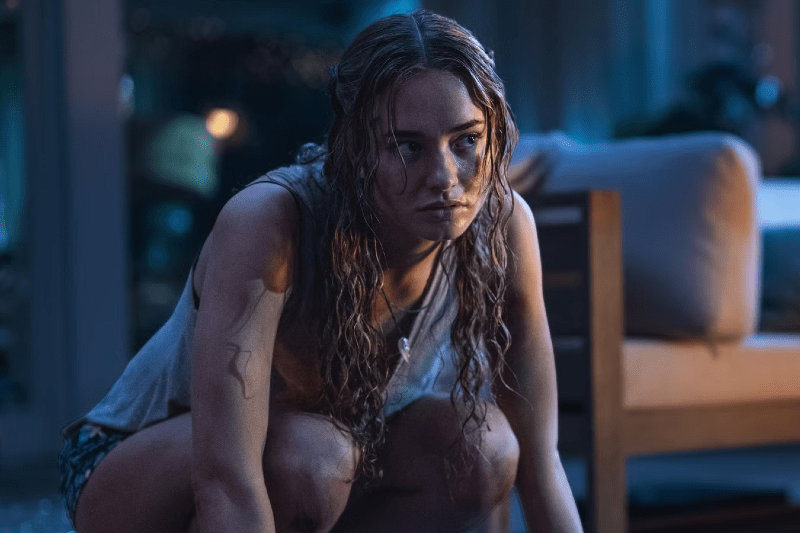

Shot by cinematographer Andrew Scott Baird, Stuckmann’s individual scenes feature sparks of fun, and moments where shadows and reflection become genuinely frightening, even though the movie ultimately opts more for startles than actual scares. Sullivan, who plays Mia, adds some important dimensions too, between her determination to find her sister, and her shaky breaths and physical tremors, which imbue scenes illuminated by flashlight (and textured by cold breath) with a certain electricity. The problem, however, is that Sullivan’s incessant shivers become the focus of one too many close ups that linger too long without much by way of creeping, building dread. The result feels more overcaffeinated than actually hair-raising.

There’s nothing particularly wrong with Sullivan’s performance, but she’s seldom directed to do anything engrossing. Mia never exists as a multifaceted person beyond her plot function, and beyond the broadest possible motivations when it comes to finding her sister. In demonology terms, it’s hard for the audience to latch onto such a blasé host. It certainly doesn’t help that the movie’s larger, scene-to-scene structure lacks momentum, despite having life-of-death stakes. Rather than a coherent causality pushing Mia between scenes and places, she’s usually flung between them with little sense of time, space, or rhythm, giving Shelby Oaks the sensation of a free-verse montage experiment, when something tighter would have benefitted its tone. It’s disorienting, but not in a way that feels intended or earned. These inconsistencies infect specific shots and moments too, occasionally robbing tension during scenes of travel, transition, and discovery. A more fine-tuned edit could have theoretically led to Shelby Oaks feeling like more of a journey, rather than a ramshackle collection of spooky happenings, but the culprit appears to be the existing footage, rather than how it’s cut together. An awkward jump here. A confusing transition there. Some of the pieces simply don’t fit.

Despite the movie’s highlights and eerie moments, its rote and literal answers make for a far-too-obvious (and far-too-derivative) October offering that signals, to its audience, that it knows exactly the kinds of things they usually enjoy. It tries to re-create these delicacies on a sampling platter, but uses cheaper ingredients. The result is not entirely untoward, given how effective some sequences end up being, but if Stuckmann is going to stick around in the horror space, it’s probably good that he’s gotten these overfamiliar clichés out of his system. The promise of the movie’s first twenty minutes gestures towards him having something much more interesting, unique, and self-reflexive to offer, so it’s hard not to hope he channels those instincts at some point, instead of condensing every WatchMojo Top 10 Horror Movies list into a single film. [2.5/5]