Given that it's a recent entry in the queer horror canon, it’s a bit surprising you don’t hear more about 2019’s Shudder original Spiral. A tense horror-slash-mystery, Kurtis David Harder's Spiral pushes the boundaries of the unreliable narrator, using the homophobia of the ‘90s as a springboard to explore deeper suburban terrors. With its social consciousness on its sleeve, Spiral works hard to be a film with something to say; and it is, literally begging viewers to heed its warnings. But these messages are larger than the fantasy story they’re embedded in, tiptoeing so close to real life it’s scary.

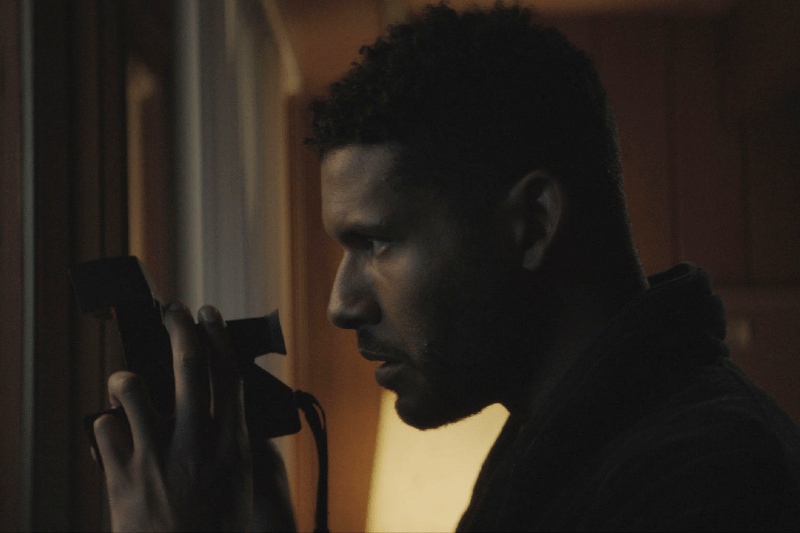

Spiral opens on same-sex couple Malik (Jeffrey Bowyer-Chapman) and Aaron (Ari Cohen) as they arrive in a new town with disaffected teen daughter Kayla (June Laporte) in tow. Rusty Creek is a sleepy place—quiet and serene. But instead of lowering his guard and relaxing, Malik almost immediately feels unsafe, the neighborhood residents vaguely threatening. Which is valid; the year is 1995, and most conversations have an air of judgement about them. Two men living together? Scandalous! It doesn’t stop there, as soon Malik is faced with a break-in, a slur spray painted on their wall. But since Aaron and Kayla seem to be having a great time – easily acclimating and making new friends – Malik keeps his concerns to himself. And keeps Aaron in the dark.

It's established pretty early on that Malik is not OK. Via flashbacks to his teenage years, we learn that he was the victim of a hate crime, his wounds never truly healing. It colors the way he relates to the world, something Aaron, who has seemingly never faced the same explicit bigotry, can’t seem to understand despite their loving and communicative relationship. So when things begin to feel weird in the new house, Malik leans in, his distrustful nature taking the lead. Unfortunately, his prior trauma and paranoia make him easy to dismiss, and as he continues to keep things to himself, his story becomes less and less believable. Until he’s totally isolated.

While Malik feels like an unreliable narrator, much of what drives him is grounded in reality. The painted slur, cryptic warnings, a cult-like ceremony — they’re things he sees, as well as documents. Still, it isn’t enough for the people around him, because by the time he reaches out in earnest, Malik is too far gone. His ramblings about cults and manipulation sound like the rantings of a deeply unwell individual, and as his behavior escalates, Aaron kicks him out.

Spiral does an exquisite job planting seeds of doubt. Even though the viewer sees what Malik sees, we’re often asked to ignore it. Excuse it. Rationalize it away. At one point, Malik points a gun at a shadow, its shape devilish and threatening. He’s about to pull the trigger when the shadow shifts, changing into the silhouette of a person kneeling. It’s a watershed moment, a fork in the road. Is this man sane? Is any of this real? But just as Malik’s grip on reality feels most tenuous, he finds his prescription medication has been tampered with.

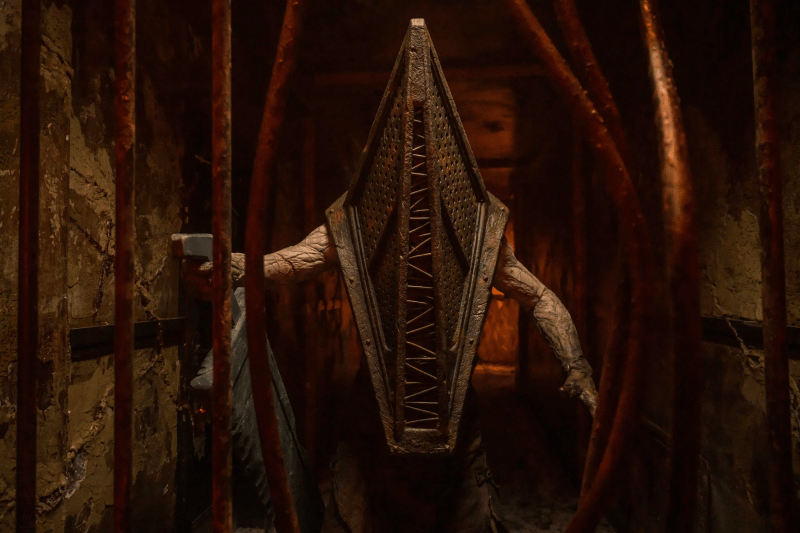

While Malik may often present as unreliable, the narrative is anything but ambiguous, explicitly stating everything Malik has feared is, in fact, true: his family is being targeted by a cult, the titular “spiral” their symbol. With the ambiguity dissolved, the film’s true horror is allowed out in the open. The break-ins, the dead animals, the loaded glances are child’s play once the cult’s true motivations are revealed.

The spiral represents a cycle. Every 10 years the cult’s leaders mark a neighborhood family for sacrifice. Every 10 years, the group targets a new brand of “undesirable.” Malik uncovers information about the victims from 1985, a lesbian couple and their daughter, reviewing VHS tapes that chronicle their eerily similar experience. In 1995, Malik is living the same thing, careening haplessly toward a predetermined outcome, the spiral’s inevitably less a warning and more a promise.

After Malik goes off the deep end, shooting his neighbor Marshal (Lochlyn Munro) in the chest, he winds up in jail. In his absence, the cult finally reveal themselves to Aaron, appearing in his home, their youngest member elbow deep in Kayla’s chest cavity, literally consuming the young woman. At the same time, Marshal shows up — alive — to visit Malik in lock-up. With the cycle complete, he’s very clear about their motives, revealing just how large the spiral truly is.

One of the most upsetting aspects of Spiral is its bleakness, often so suffocatingly hopeless it feels nihilistic. The cult expertly dismantles both Malik’s loving relationship and his mental health, sending him into a spiral of his own. They weaponize his paranoia and tug at his loose threads. They toy with the family, reducing them to players on a stage of the cult’s building. But perhaps worse than the despair is the utter disinterest Marshal and his family have for the people they choose to ruin. As surprising as it may seem, they have no issues with queer people—truly. They have no ill will, no judgment. Instead, they embrace their roles as opportunists, choosing every 10 years to target whatever new flavor of undesirable they can pin their crimes on. While they present themselves as ambivalent, the group is anything but, using the most vulnerable as scapegoats for their occult cannibalism.

Despite Malik and his family’s tragic end, suffering a nearly identical fate as the lesbian couple 10 years prior, we’re presented with a glimmer of hope – and a call to action. You see, even as Malik was in the throes of a mental breakdown, he was making copies. Documenting. Building an entire dossier on the cult and the repeating tragedies. He stashes a copy in the house in hopes the next tenants will find it and break the cycle. As the film ends, it jumps forward to 2005, all eyes on the new arrivals — a South Asian family — as the cycle begins anew.

At its core, Spiral is a warning. And that warning sounds so loudly it bleeds through the screen. It’s not lost on me that this year, 2025, is part of the spiral, a never-ending wheel that feeds a rotating cast of “disposable” people to the elites. Malik saw it, but struggled to articulate the dangers, the paranoia of existing while gay making his fear appear unfounded. Even in the grips of despair, Malik fought, transmuting his hopelessness into defiance. Malik spent his last days pushing out a warning, decrying, “Hope is never silent.” He may have failed in 1995, but his hope lives on in the hearts of those willing to stand up and fight.