There’s a hidden double meaning to the title of Xia Magnus’s Sanzaru. Taken from the Japanese proverb best known as “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil,” the accepted meaning of the saying is that one should live a good life untainted by evil. But if that were true, why isn’t there a fourth truism, one that calls us to do no evil? The other interpretation of the phrase is that one should turn a blind eye and ear to evil and never, ever speak about it.

It’s that second, darker meaning that pervades Sanzaru, the 2020 debut feature from writer-director Xia Magnus. In the film – a subdued and somewhat experimental take on the Southern Gothic ghost story – two families live in the same house and grapple with dark secrets. But it’s only the one who can name those evils that has a chance at survival.

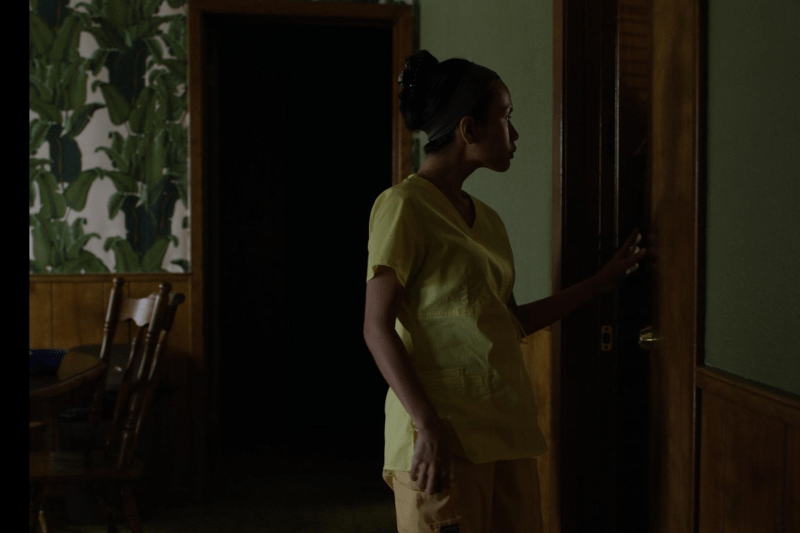

Shot near the south Texas town of Victoria, Sanzaru approaches the tropes of the Southern Gothic – an old house, characters hiding secrets, ghosts of the past – from a fresh perspective, that of a Filipino-American immigrant. Evelyn (Aina Dumlao) works as a home health aide for an elderly woman, Dena (Jayne Taini), living in a house so remote that even the mailman doesn’t go out that far from town.

Magnus is not of Filipino descent, and in interviews he has said that he was interested in writing about the sort of live-in caregivers who used to care for his grandparents. Those workers, often immigrants in Magnus’ experience, are privy to the most intimate moments of a family’s life and, in many ways, are treated as family. But in other ways, they’re not. They occupy a fluid and uncertain position that mirrors an immigrant’s standing in America – welcomed as part of the country but treated as an outsider, sometimes when it matters most.

The film’s prologue opens on a dark country road; ominous ambient sounds fill the score before we focus on an old cemetery behind a chain-link fence, choked with weeds. We then see a woman’s body in a casket, followed by her voice and a glowing ball of light. “Did you invite me?” the confused voice asks. “What are we doing here?” The response from another spirit is a burst of white noise and an angrily flashing red light. It’s an atmospheric opening scene that showcases Magnus’ skill with using haunting sound design to compensate for a limited visual effects budget.

From this elusive prologue, we’re shaken awake into Evelyn’s real life, uncertain whether what we just watched was her dream or something else. As she goes about her day, the viewer begins to understand these people and their relationships to each other.

In the early part of the film, Magnus takes care to chart the relationship between Evelyn and Dena. We see Evelyn and Dena hold hands absent-mindedly as Dena watches an old movie on television while Evelyn works on a crossword with her free hand. They could be family. But in another scene, Dena asserts her authority over Evelyn as an employer.

Dena’s dementia is unpredictable – in one moment, she can not only provide the answer to one of Evelyn’s crossword clues (“CONSONANCE”) but spell it correctly. The next moment, she mistakes Evelyn for her daughter and asks when her brother will be home from school. Throughout, both actresses are terrific. Dunlao captures the empathy but also the reserve that Evelyn must maintain as a live-in caregiver. Taini shows Deni’s fear and embarrassment as she realizes her mind is flickering on and off like the unreliable electricity in the house.

Another resident of the house is Evelyn’s nephew Amos (Jon Viktor Corpuz). He’s a sullen teenager who has moved in after a violent incident at his Dallas high school. He goes on punishingly long runs to avoid spending time at home. We also meet Dena’s son Clem (Justin Arnold) also lives in the property, but he’s not of much use. An Iraq War veteran suffering from PTSD, Clem lives in a camper out in the yard, tortured by his memories. Of the film’s deceased patriarch, little is said.

Amos and Clem’s instincts to avoid the Regan house seem sound, even before the supernatural happenings start. You can almost smell the mildew in the gloomy house, and inhale the dust from spare rooms stacked with boxes that haven’t been opened in years. Magnus’ sound design magnifies the sad eeriness of the house. Silences are punctuated by the groan of the furnace turning on or the chirp of a dead smoke detector battery in the night.

An ancient intercom system connects the rooms in the house, the plastic faceplates yellowed like stained porcelain. Late at night in her room, through the buzz of static, Evelyn can hear Dena’s frantic babbling (“I’m scared all the time. I wish you hadn’t told me”) to empty air. Then a new voice begins whispering through the intercom to Evelyn, a woman’s voice speaking in her native Tagalog. At first, the voice is too faint to recognize, but as it grows insistent, Evelyn realizes it’s the voice of her mother, who died the year before in the Philippines.

And that other, malevolent presence represented by the angry red light is also present. Picking up the family’s mail in town, Evelyn finds a letter addressed to a “Mr. Sanzaru.” Evelyn begins looking into the secrets of the Regan family, opening up closed-off rooms and digging through stained boxes. It becomes clear that both families are haunted by their own secrets – and their own spectres.

Sanzaru is less of a horror movie and more of a ghost story wrapped around a family drama. While there are a couple of jump scares, the film plays out as an eerie mood piece. Magnus does ratchet up the tension with the occasional shock, such as the unfortunate fate that befalls Dena’s beloved cockatoo. But those jolts are only effective because of the careful groundwork of emotional tension that has already been laid.

The film’s biggest risk is its third-act plunge into more overt horror when that flashing red light – dubbed “Mr. Sanzaru” – becomes a red humanoid shape that prowls the house. An image of the monster perched on the end of Dena’s bed, like the devilish creature in Henry Fuseli’s painting The Nightmare, is particularly nerve-rattling. The spirit of Evelyn’s mother – that glowing ball of white light – also manifests itself to wage a poltergeist proxy war between the two families.

Whether this ghostly battle of wills is actually happening or playing out in Evelyn’s subconscious as she wrestles with her allegiances to Dena’s family over her own is left for the audience to puzzle out. Sanzaru is in many ways a bleak and ambiguous film, but it offers a clear path to dealing with evil that lives among us – not to turn away, but to see it, to hear it, and to speak it.