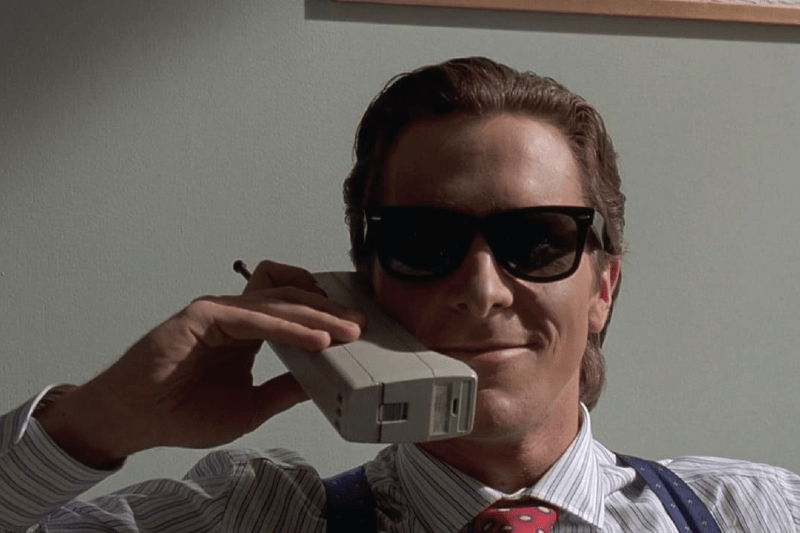

American Psycho’s Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale) and Man Bites Dog’s Ben (Benoît Poelvoorde) live, for the most part, vastly different lives. American Psycho is a serial killer story in shiny 2000s American cinematic packaging. Our protagonist is played by a movie star and surrounded by other movie stars, including Reese Witherspoon, Willem DaFoe, and Jared Leto. Patrick is ultra-wealthy but certainly not self-made, living off the privileges of his father’s money and connections. He’s surrounded by the wealthiest and most beautiful of Manhattan, and, hollow as can be within, kills to satiate a bloodlust that often seems to be the only activity that meaningfully stimulates him.

Man Bites Dog, on the other hand, is cheaply made and simple, shot in black-and-white and presented as one of the earlier contributions to the mockumentary/found-footage horror canon. The production is tiny, self-enclosed, as Ben and the director that follows him, Remy (Rémy Belvaux), are both played by the actual directors of the film. In Man Bites Dog, Ben is a member of the working class in 1990s France, followed around by a documentary crew with minimal resources, living the serial killer equivalent of paycheck to paycheck as he kills people for pleasure and then ransacks their home for cash.

Despite these aesthetic differences — and despite the geographical and class differences that make the two characters culturally worlds apart — Ben and Patrick align in two key ways: both men have an unrepentant, unstoppable lust for killing, and both men are annoying as all hell.

In between their grisly murders, we are pervaded with Patrick and Ben’s boring, overconfident belief systems. The two love explaining who they are and what they believe, both to their canonical captive audiences (friends, sex workers, and secretaries for Patrick; an indebted film crew for Ben) and to us, as Patrick pervades our space with a voiceover, and Ben frequently talks at the camera. After a brutal montage of Ben shooting an endless amount of people, he launches into a spiel on low-class housing, on the way that the government has failed its poorer communities by not giving them aesthetically pleasing spaces to live.

In one of the more iconic American Psycho moments, Patrick Bateman pontificates about his love for Huey Lewis and the News’ “Too Hip to Be Square” to a bored, drunk, half-listening Paul Allen (Jared Leto) before murdering him. His analysis, shouted over the music playing uncomfortably loudly, is not interesting or special, it mostly sounds like it’s ripped directly from the Culture Sections of the newspaper that Patrick spreads on the floor for easy clean up post-murder. It’s almost a relief when Patrick starts bashing Paul’s head in, so self-centered is his rant about a single pop song.

American Psycho and Man Bites Dog are certainly not unique in their exploration of both a serial killer hiding in plain sight or their representation of masculinity in crisis, but they do stand out in the sense that said killing and said masculinity in crisis is based in a sort of narcissistic overconfidence, a vastly fragile, hollow, and irritating ego. These men do horrible, violent things, especially to women, especially to working class people. But the way they act, the nonsensical belief systems they constantly share, cause them to crawl under our skin in a terrified way, but also an irksome one. Their entitlement and ego is what stands out. You want them to get away from you less because of fear, more because they’re exhausting to be around and listen to — a sensation often reflected in the people they hang out with.

When Patrick hires some sex workers and has them chat and sip wine in his living room, he asks, “Don’t you want to know what I do?” The two women share a glance. “No,” one of them responds. “No, not really,” the other quickly agrees. He bores. He wastes their time. He answers anyway, too proud to resist. “Well, I work on Wall Street”.

Remy rarely responds to Ben’s monologues, opting to tune him out — not that Ben ever notices, choosing to recite poems about pigeons in the middle of a shootout or mock Remy for the way he laughs, hypnotized by the sound of his own voice.

This endless spewing of beliefs is not only annoying, but points to a unique hollowness in both of these portrayals of serial killers. It is not that they have something special or interesting about them that makes them kill. Instead, these obnoxious killers seem to kill because there is absolutely nothing brewing beneath the surface. It’s all ego and narcissism, no insides. Patrick iconically acknowledges this outright in one of his pervasive voiceover monologues, explaining:

“There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman; some kind of abstraction. But there is no real me: only an entity, something illusory. And though I can hide my cold gaze, and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable ... I simply am not there.”

Patrick Bateman

For Ben, this need to be validated without being seen for his true, meaningless self is reflected in the very premise of the documentary. He often references that he is partially funding the documentary himself, seemingly certain that his perspective and experience is important — despite this perspective being not just grating and endless, but inherently conflicting. He both feels that the working class are a lonely group that are not cared for by the government and community, while solely targeting working and lower class people because no one notices “the small fry” going missing. Creating a documentary allows for Ben to spew nonsense at both the indebted crew and viewers without risk of his ego being deflated or questioned by his captive audience.

When either Patrick or Ben’s egos are deflated, they are at their most dangerous. Patrick’s murderous loathing of Paul Allen stems from something as silly as Allen’s business card looking nicer than his, and when a guest at Ben’s small birthday party takes up attention with brash confidence, laughing loudly, catching the eye of Valerie (Valérie Parent, playing a woman who Ben has a paternal fondness for), Ben’s usual insistence upon controlling the energy of the space and people he’s around is derailed. In turn, Ben unceremoniously shoots the man in the head, ensuring attention is once again returned to him.

Both Man Bites Dog and American Psycho label themselves as satirical, as black comedies. They are not meant to strike the usual anticipated fears we have about serial killers. Patrick’s spiels about Huey Lewis and The News, about his skin care routine, Ben’s poems, and conflicting monologue about class systems are meant to elicit some knowing laugh, to poke at a person we probably personally know. The type of person so entrenched in being perceived as someone who knows things, who knows themselves, but actually is totally unaware of their off putting and inaccessible narcissistic nature.

American Psycho and Man Bites Dog look at a specific crisis of masculinity — the cultural requirement that a man be wholeheartedly confident in matters of life, self, sex, and culture, so confident that no one else needs to be listened to, empathized with, or valued — and consider if this specific, irritating way of being is not only an annoyance, but bordering on dangerous in its fragility.