Looking back from the vantage point of twenty-five years past, it’s easy to see how right Hunter S. Thompson was when he declared the party over in the aftermath of the World Trade Center collapse. Yet of the countless movies that expressed a pre-millennial anxiety towards the end of the 20th century, few could conceive of the grinding economic uncertainty that would come to characterize the decades ahead. This makes In The Dark, Clifton Holmes’s virtually unseen SOV adaptation of the novel by Richard Laymon, so uniquely compelling: it presents a twilight vision of America perched at the extreme edge of an economic and moral abyss.

One evening, bored librarian Jane (Kim Garrett) finds her routine of sharpening pencils and re-shelving books interrupted by an envelope left at her workstation. Ripping it open, she finds an invitation from someone calling themselves Master of Games (MOG), inviting her to play with him. Following the letter’s instruction to “Look homeward, angel,” she discovers another envelope stashed in a copy of Thomas Wolfe’s novel of the same name, containing a second note and two fifty dollar bills.

Initially thinking it might be a prank by Brace (Alex Ellerman), the young man she bumps into in the stacks, Jane brushes off her skepticism and asks him to help her decipher the clue to the next envelope. As Jane travels further down and further down MOG’s road to riches, the monetary amounts she finds grow exponentially, but so too does the danger of the situations the clues put her in.

In the Dark is one of those increasingly rare shot-on-video efforts that, even in our golden age of boutique physical media and streaming, has never had a proper release on home formats. The movie reportedly never played theaters outside of screenings at the Chicago Underground Film Festival and San Francisco Indiefest and was never even copyrighted, making the film a true blue off-the-radar hidden gem. In the Dark has been kept alive thanks to word-of-mouth from fans of SOV horror – and unlabeled DVD-R sellers on eBay, whom we thank for their service – heightening the elusiveness and mystery of the product and only adding to the mystique.

But to chalk In the Dark’s reputation up to its scarcity would be to discount what a marvel of nightmarish, no-budget creep-itude it is. Holmes –like Eduardo Sánchez and Daniel Myrick of The Blair Witch Project did at practically the same moment – saw an opportunity to turn the consumer grade format’s inherent limitations into nightmare art. His approach, however, is notably more classical and formalist than The Blair Witch Project’s verisimilitude, with a deft handling of story, image, and tone that puts most SOV efforts to shame.

Filmed in the Chicago area and utilizing DePaul’s John T. Richardson Library, Wunder’s Cemetery, and Northwestern student haunt Yesterday’s just before its closing, In the Dark has an on-the-ground, regional flavor that money can’t buy. Yet, at the same time, the world Jane inhabits is rendered anonymous and chokingly small due to the film’s monochrome photography and limited cast – visually reflecting the hollowed out loneliness of its heroine as a twilit, quasi-apocalyptic no-place.

Holmes knows the muddy grain of his chosen format is an asset. Many of the low-light images are hard to parse, but he manages to punctuate his grubby lo-fi creeper with a tapestry of indelible images – a gun in a freezer, an amputated leg, a mask in the dark. Editing is the real star here. Though In the Dark features plenty of dialogue lifted directly from Layman’s novel, there are also extended sequences when Garrett is totally alone with little more than the film’s aural landscape of video buzz and ambient noise to accompany her. Here Holmes uses cuts and interruptions to draw us ever further down her rabbit hole. Though largely scoreless, the film’s transfixing expanses of silence are often broken by isolated pops on a snare drum to intense and driving effect.

Garrett, however, is Holmes' ace in the hole. Information on Garrett is even less than scanty, and, beyond a mere handful of assorted credits to her name, it seems that she was and remains something of a non-professional actor. In the Dark was her film debut and she gives what is easily one of the most compelling performances in the SOV canon. With a downturned mouth and darkly circled eyes, her Jane is at once dispirited and fanatical; world-weary enough to know she’s being taken for a ride but humming with an almost indecent excitement at knowing where she might end up. She makes it as easy to believe that Jane is drawn into the game by the promise of wealth as it is to recognize a deeper, seedier desire in wanting to lift the rock of hum-drum normalcy and see what’s crawling underneath.

Sexual violence and the objectification of women dance around In the Dark’s murky edges until they take center stage in the film’s most overtly horrific sequence. Early on, MOG sends Jane to a stranger’s house, ordering her to present herself to him as a servant to “use” until midnight in any unspecified way he wishes. Later, a “fabulously wealthy” male jogger – who later turns out to be a gimp-suit wearing agent of MOG’s – offers to pay Jane for her time should she accompany him to his mansion.

The inherent threat in these exchanges becomes overt when MOG sends Jane to a literal house of horrors. Given an address and not much else to go on, Jane arrives at an upper-middle-class suburban home where she finds a group of women in various states of mental distress and physical mutilation. One has been forcibly impregnated, another is consuming her own severed arm, and, most disturbingly, another is literally rendered an object: limbless, left in a suitcase with her head peeking out, and placed in a corner like a ghoulish piece of furniture.

The letter that MOG leaves for Jane at this revolting scene is characteristically flippant, suggesting that boys will be boys. After Jane rescues the women, she can’t resist the opportunity to exact some righteous female vengeance against the perpetrators, who are all hanging out in the basement – Holmes himself among them –stripped to their tighty whities and watching a bizarre musical burlesque. Jane’s execution of these men is a moment of satisfaction for the viewer and plays out largely in the same way it does in Layman’s novel, but the manner in which the film’s climax diverges from the author’s original vision adds a disturbing sense of pointlessness to this moment.

In the Dark the novel concludes with a protracted church shootout in which Jane and Brace manage to kill MOG’s gimp-suited compatriot and face MOG himself – a vampirish figure whose head they strike from his body and bury in hallowed ground, allowing them to escape with money and free of MOG’s unholy influence. Conversely, in Holmes’s cinematic version, Brace disappears, with MOG attaching his severed ear in a note to Jane. In an attempt to save him, she forsakes the roadside motel the two spent the night in, only to come face to face with the gimp, who she executes, but a happy ending is not in store.

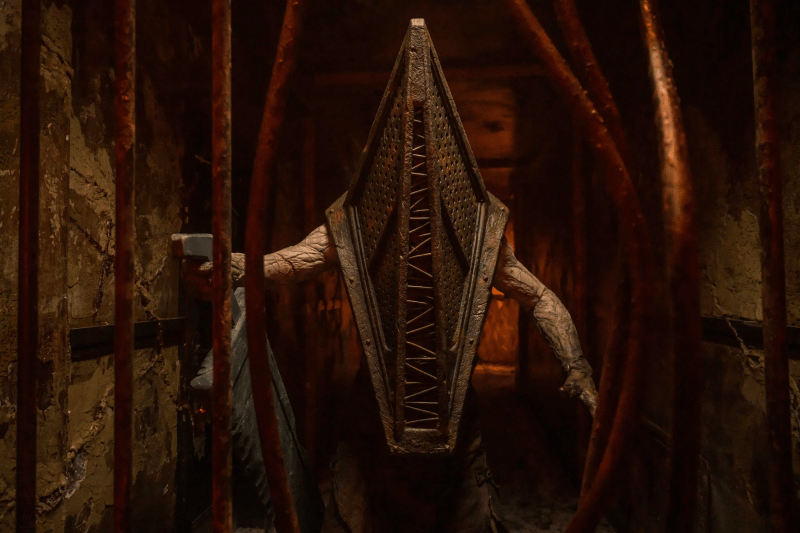

We get a brief glimpse of a silvery wig and axe before the film’s most blood-chilling moment. A time card indicates a jump of more than a year, showing us that Jane is still carrying out MOG’s tasks: leaving letters with other unsuspecting people and luring them into his dark games with the same promise of fabulous wealth and excitement that ensnared her. The film’s final minutes show Jane alone in a high-rise apartment, a pile of envelopes full of money tossed mindlessly in a closet, playing Silent Hill all by her lonesome, the character on screen wandering aimlessly.

What are we to make of this ending 25 years on? In the Dark was finished years before the 2008 financial crisis and a decade before the massive wealth gap in the U.S. became a conscious concern for most Americans. As of this writing, the GOP’s humorlessly named “Big, Beautiful Bill” is primed to usher in the greatest transfer of wealth from the poorest Americans to the billionaire class in our country’s history. These are realities far beyond the scope of what Layman or Holmes could have envisioned, but in the film adaptation’s cynicism there’s a timeless truth that can speak to our current moment.

The more Jane plays along, the more money she herself acquires, and the less she should need to bend to MOG’s will. But in our capitalist hellscape, the only choice is between exploiter and exploited, and history tells us which of the two options any sane person would prefer. The game leaves her richer, but no better off than when she started, beholden to a shadowy power system she’ll never understand. She may be a victim, but she is also a silent conspirator. The party, for many of us, is indeed over. But for those with the capital and influence to keep pulling the strings, it won’t end till they snap.