‘Infection’ Is a History Lesson In Authoritarianism

Ursula Muñoz S. examines the violent history of Venezuelan authoritarianism that drives Flavio Pedota's 'Infection.'

Jump Into Certified Forgotten

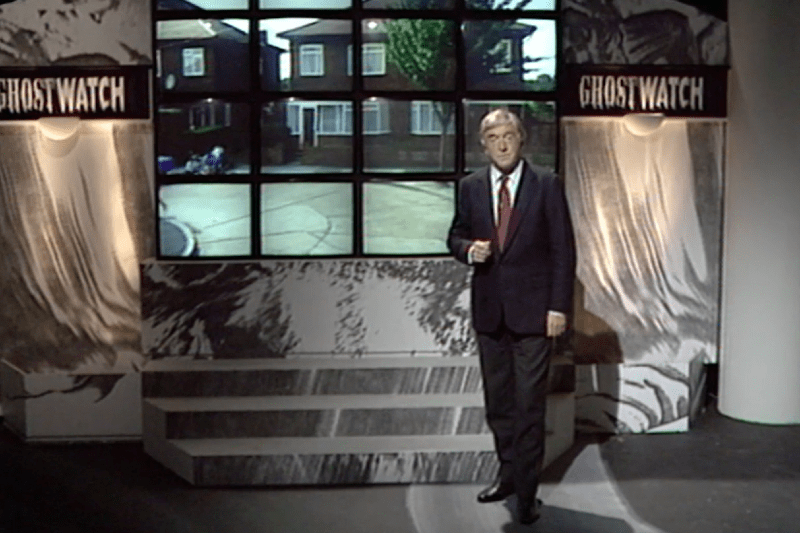

Podcast: Kate Siegel on ‘Ghostwatch’

'V/H/S/Beyond' filmmaker Kate Siegel joins Certified Forgotten to talk about her directorial debut and Lesley Manning's 'Ghostwatch.'

Podcast: David Dastmalchian on ‘Entrance’

'Late Night with the Devil' star David Dastmalchian joins Certified Forgotten to discuss 'Entrance,' one of his favorite underrated slashers.

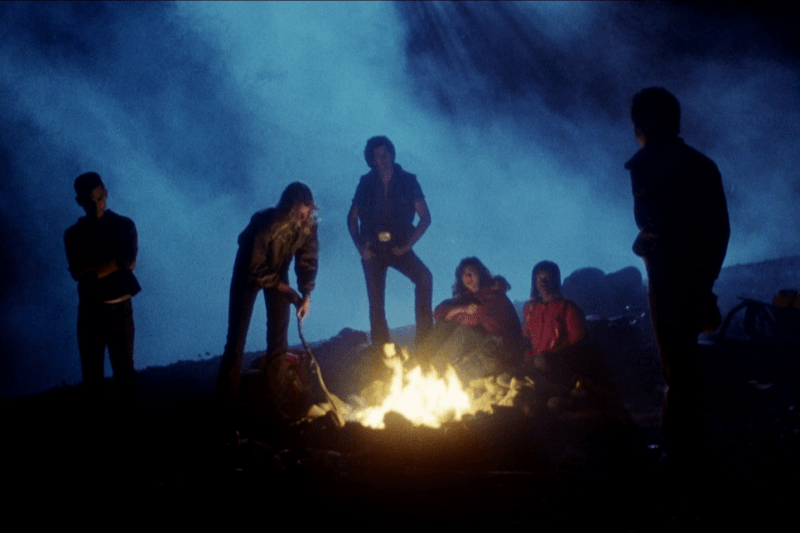

Podcast: C. Robert Cargill on ‘The Final Terror’

Screenwriter C. Robert Cargill ('The Black Phone') joins Certified Forgotten to discuss Andrew Davis's anti-slasher 'The Final Terror.'

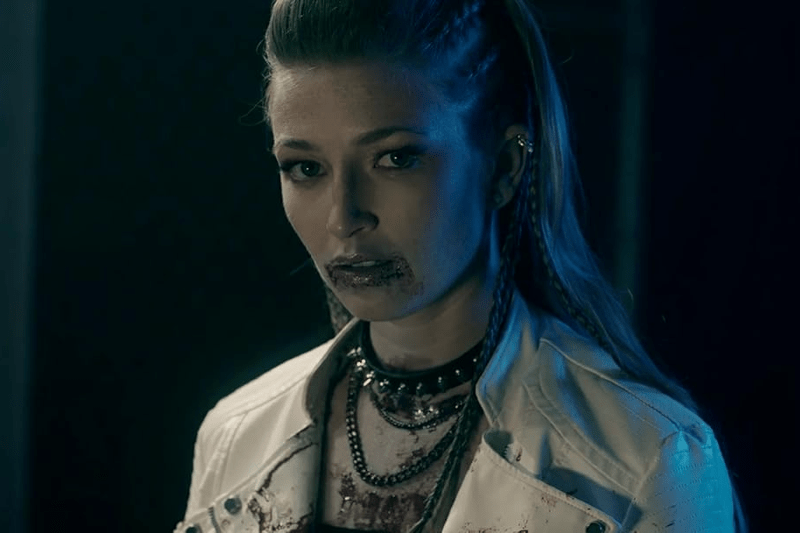

Podcast: Aimee Kuge on ‘Shatter Dead’

Aimee Kuge ('Cannibal Mukbang') joins Certified Forgotten to talk about her debut feature and Scooter McRae's cult classic 'Shatter Dead.'

Four for Your Watchlist

Uterus Horror

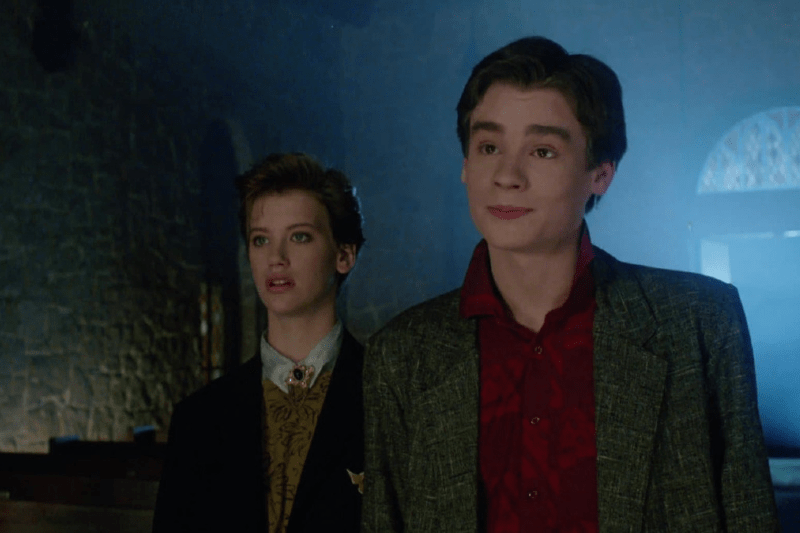

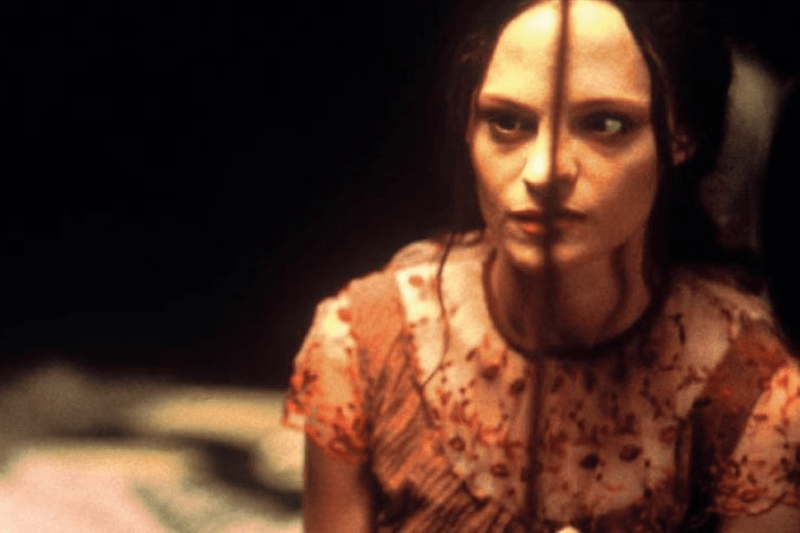

The Absent Adults of ‘The Blackcoat’s Daughter’

In her latest Uterus Horror column, Molly Henery digs into the absent parents of Osgood Perkins's 'The Blackcoat's Daughter.'

New Articles

How ‘Project Silence’ Blends Disaster and Horror

Kim Tae-gon's 'Project Silence' blends the disaster movie with horror to create an issue-driven blockbuster for the masses.

Podcast: Matthew Jackson on ‘Pale Blood’

Film critic and Scares That Shaped Us host Matthew Jackson joins the podcast to discuss V. V. Dachin Hsu's 'Pale Blood.'

Podcast: ‘Sinners’ Gets Uncertified

In this episode of Uncertified, Matthew Donato and Matthew Monagle discuss Ryan Coogler's 'Sinners,' the movie of the summer.

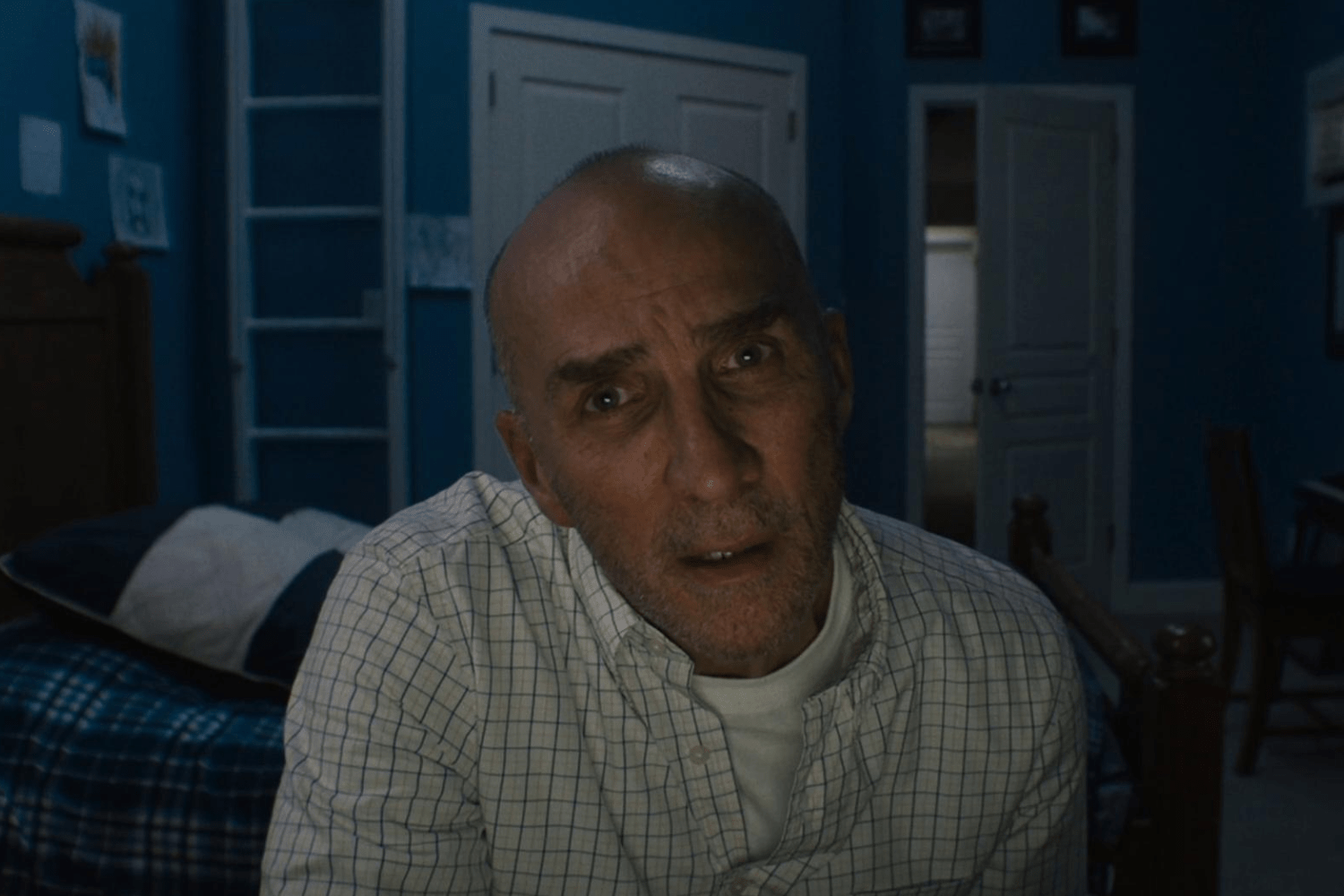

In ‘Blood Curse,’ Evil Is an Act of Faith

Often marketed as the first Portuguese horror film, Tiago Guedes's 'Blood Curse' is an ambiguous exploration of generational sins.