Mrs. French’s Cat is Missing: Words as Weapons in ‘Pontypool’

Contributing editor Christine Makepeace explores the primal power of language in her essay on Bruce McDonald's 'Pontypool.'

Listen to the Certified Forgotten Podcast

Podcast: Kate Siegel on ‘Ghostwatch’

'V/H/S/Beyond' filmmaker Kate Siegel joins Certified Forgotten to talk about her directorial debut and Lesley Manning's 'Ghostwatch.'

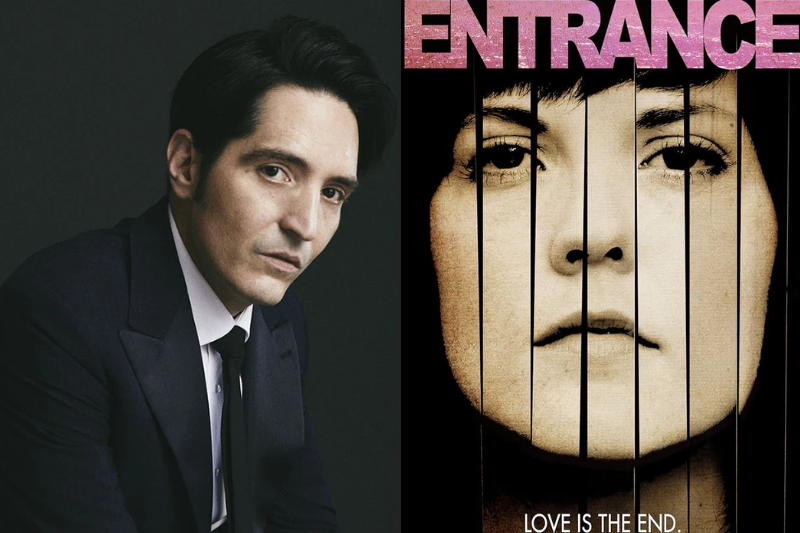

Podcast: David Dastmalchian on ‘Entrance’

'Late Night with the Devil' star David Dastmalchian joins Certified Forgotten to discuss 'Entrance,' one of his favorite underrated slashers.

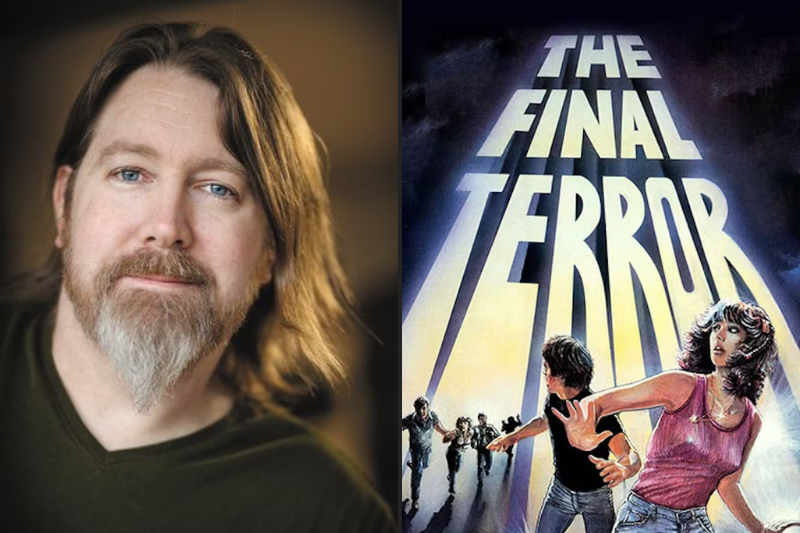

Podcast: C. Robert Cargill on ‘The Final Terror’

Screenwriter C. Robert Cargill ('The Black Phone') joins Certified Forgotten to discuss Andrew Davis's anti-slasher 'The Final Terror.'

Podcast: Ryan Prows on ‘Los Bastardos’

Writer-director Ryan Prows ('Night Patrol') joins the podcast to talk about vampire cops and Amat Escalante's 'Los Bastardos.'

New Articles

Podcast: Tori Potenza on ‘The Cremator’

Film critic and programmer Tori Potenza joins Certified Forgotten to discuss Juraj Herz's antifascist horror film 'The Cremator.'

‘Diabolic’ Review: Uneven Balance of Religious and Gonzo Horror

Daniel J. Phillips's 'Diabolic' sets its sight on fundamentalist Christian groups but can never quite commit to a subgenre of horror.

‘Salvation’ Review: A Haunting Gaze at Violent Persecution

Through dreams and nightmares, Turkish filmmaker Emin Alper explores political violence in ‘Salvation,’ his bleak vision of human hatred.

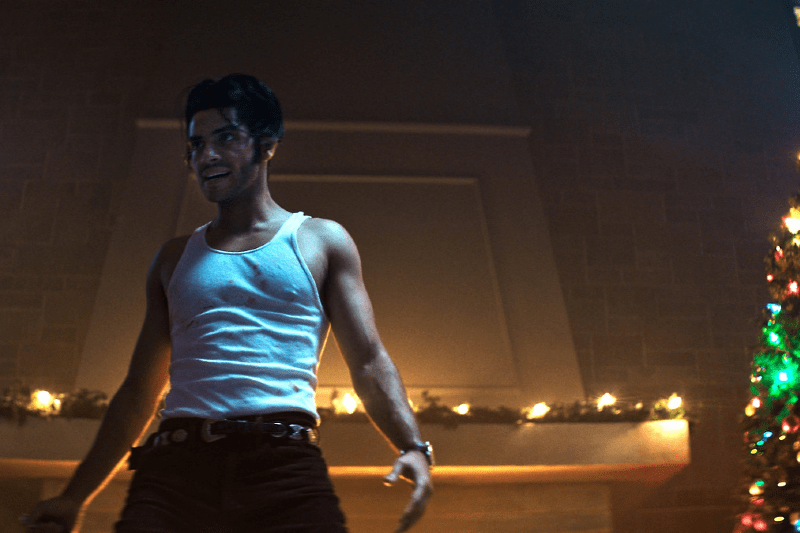

‘Ghost in the Cell’ Review: Indonesian Action-Horror-Comedy Nearly Sticks the Landing

Joko Anwar’s anything-goes genre mashup ‘Ghost in the Cell’ laces prison drama with political commentary, dance routines, and bloodshed.