“My name is John Harrington. I am 30 years old. The fact is I’m completely mad.”

From the opening moments of Hatchet for the Honeymoon, Mario Bava seems determined to break the rules of the subgenre he helped create. In (formally!) introducing the killer to us, Bava completely eliminates the whodunnit element from the giallo. Bava even goes a step further, turning the genre on its head by using our suspected antagonist as the protagonist. Throw in his focus on humor and the lack of a mask or black gloves, and it is no wonder why some purists believe Hatchet for the Honeymoon doesn’t really qualify as a giallo.

But let’s not forget that Bava’s contribution both to horror and exploitation cinema is immeasurable. The Italian filmmaker broke new ground for gothic horror with 1960’s Black Sunday; he also pushed the envelope in loading a mainstream movie with clear S&M overtones in 1963’s The Whip and the Body. But no contribution would be greater than that of his signature genre, the giallo, laying out the prototypical foundation in 1963’s The Girl Who Knew Too Much then the archetypical one in the following year’s Blood and Black Lace.

And when you invent something, you also get to make — and break — your rules at will. As Father of the Giallo and Grandfather of the Slasher, Bava would constantly evolve and reinvent his genre. But the most daringly distinct element of Hatchet for the Honeymoon is how Bava chose to sharply satirize his own signature genre and style.

“A woman should live only until her wedding night. Love once. And then die.”

Hatchet for the Honeymoon

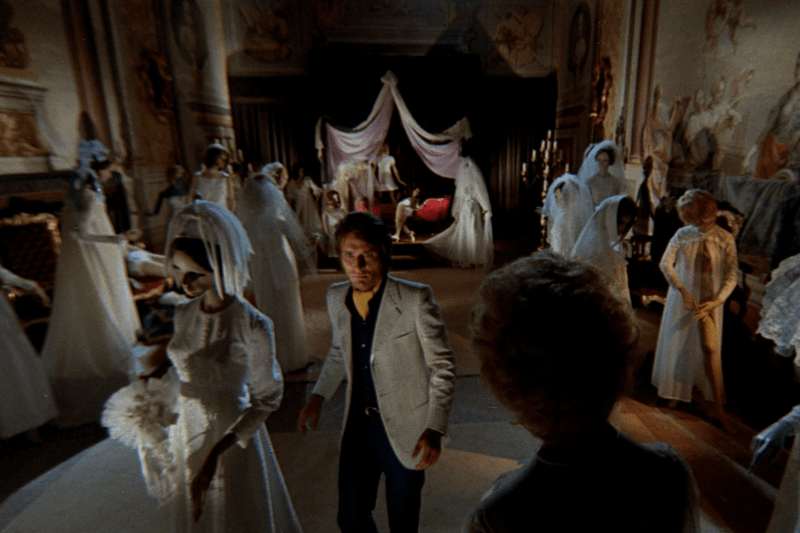

Welcome to the perversely romantic philosophy of John Harrington (Stephen Forsyth), who inherited a bridal fashion house and is always looking for new models for the dresses. Whenever any of them pass the good news that they’re to get married, he can’t help but prepare an elaborately grisly send off as congratulations.

Too bad it’s not nearly as easy to be rid of his own estranged wife (Laura Beti) who won’t allow him a divorce and pesters him every day about his affairs in both senses of the word. Not to mention Inspector Russel (Jesús Puente), who’s investigating the mysterious disappearances of model after model in his villa. Or most of all new girl in town Helen (Dagmar Lasander), who so thoroughly charms Harrington that he doesn’t even want to kill her — but her suspicious curiosity may force his hand.

“How sad. Another bride killed….but fortunately, she paid for her wedding dress in advance.”

Hatchet for the Honeymoon

Hatchet for the Honeymoon is just as evocatively imaginative as its title; a rare case where the English name is better than the original, The Red Sign of Madness. There’s a distinctly self-conscious, zanily humorous mood that remarkably doesn’t compromise the genre’s characteristically dark aesthetic and intense violence. Bava is poking fun not so much at himself as the inherent misogyny and materialism of the genre, giving the protagonist a psychotically ludicrous bride fetish that’s nevertheless also part of a piteous compulsion.

The film and Forsyth create a hilarious contrast between the protagonist’s utterly calm, insouciant demeanor and hyperbolic insanity. Much of the time when Harrington’s not taking out brides before “taking out” brides, he’s making out with his mannequins. The gleeful absurdity reaches a fever pitch when he goes for one particular murder in company apparel himself.

For all those quirks and deviations, it’s no surprise Hatchet for the Honeymoon was generally ignored at best and panned at worst by critics. It wasn’t just by the contemporary mainstream critics and international film circuit who were usually snobbish about Bava anyway, but even many attuned towards his work who were flummoxed by this film. To their defense, its problematic and haphazard production shows some in the cohesion of the final product; but the lukewarm response was more about it not matching genre expectations or just being too strange. Yet in reality, that was all the more reason to take heed to it. Another reason is the fact this was actually Bava’s penultimate giallo (before proto-slasher A Bay of Blood).

“Very interesting. You like horror films, do you?”

Hatchet for the Honeymoon

For its time, Hatchet for the Honeymoon aptly brought the genre in all its distinct style, (non-superficial) tropes and culture to its pinnacle. And yes, the giallo IS a culture; a unique culture of extremes uniting the high-end (with its lavish, sophisticated locations, decor and elegantly dressed women) and the lowbrow (extreme and outlandish violence, sexual content or both rolled into one).

In that way it’s reasonably reflective of Italy itself: a place with a millennia-long reputation for obsessions with religious piety and morality, some of the world’s most enduringly refined architecture, arts (opera, various luxury goods), and artistic movements (satire, the widely encompassing Renaissance, socialist realism) right alongside similar societal obsessions with sex, general vice and dominance (birthplace of imperialism, Machiavelli, the mafia and fascism).

But the culture spread beyond Italy, as this pan-European film — an Italian-Spanish co-production shot in Rome, Paris and Barcelona — demonstrates. While many (maybe most) gialli find themselves at a loss to explain exactly why all the women look and stay dressed like models and all the properties, cars etc. are so extravagant, Hatchet for the Honeymoon cleverly and naturally builds the genre tropes around its very premise. As a bridal dress company heir, Harrington is put in the perfect position (occupational and locational) to attract a bevy of beauties/victims from Italy, Spain, Germany, France, and the former Yugoslavia.

The film’s attention to detail — from the use of a real bridal dress designer in the staff to Harrington’s childlike, crudely foreboding drawings on the walls — lends it more depth than anyone was probably even asking for. (To lend the genre paradox an extra resonance, in real life the film’s extravagant villa had actually belonged to an even more murderous, delusional and quirky man than John Harrington: fascist dictator Franco during his rule’s softer waning years.)

“Death exists….And that’s what makes life a ridiculous and brief drama.”

Hatchet for the Honeymoon

In essence, Hatchet for the Honeymoon is one of the best all-around showcases for Bava’s multifaceted moviemaking talents: directing, dialogue and scriptwriting, cinematography, special effects, and set design (while he didn’t do the latter in this case, he supervised and arranged). It similarly highlights his many distinct creative moods and preoccupations with dreamscapes, the surreal, grotesque, vivid, terrifying and droll, further boosted by an enchantingly dynamic soundtrack.

All of those talents and moods reach one of their most bravura convergences in the filmmaker’s career with the mesmerizingly macabre “Dollhouse of Doom.” For all the things Harrington does in other parts of the film, it’s his cultivation of this abode for the fruits of his labor that illustrates what true madness is — and the mad genius Bava of himself.

As highly misunderstood, forgotten or never remembered to begin with as Hatchet for the Honeymoon was and more or less still is, it would nevertheless turn out to have the last laugh on the genre and industry. Even going past Bava’s direct and filtered influences on hordes of gothic horror, gialli and slashers stemming from his more famous horror films, this one would prove most precursory for the very distant horror scene of what is now today: Parodic and/or self-conscious horror that still goes to extremes has become the dominant variety of more recent years that transcends subgenre. But Bava did it here full-throttle before most anyone else even thought it was a good idea, keeping one eye firmly set on his craft even as the other stayed winked.