There is a morose honesty to much of the horror that comes out of South Korea. The adversity inherent to a country that had to struggle to maintain its independence after the second World War has influenced those who were raised from childhood on stories of the fight for survival. South Korea is similar to countries such as France, whose reckoning with their own history influenced the New French Extremity film movement; it also mirrors the wave of J-horror rooted in inherited folk tales and the looming shadow of World War II.

South Korean horror doesn’t shy away from the darkness inherent in life, and no filmmaker has made a mark more prominent than Park Chan-wook. He has become one of the most prolific and recognizable directors to tackle the complexities of family trauma, grief, shame, and human indecency. Chan-wook’s unique vision is most apparent in such outstanding films as The Vengeance Trilogy (Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, Oldboy, and Lady Vengeance), The Handmaiden, and the gorgeous and complicated vampire tale Thirst (2009).

Religion in 'Thirst'

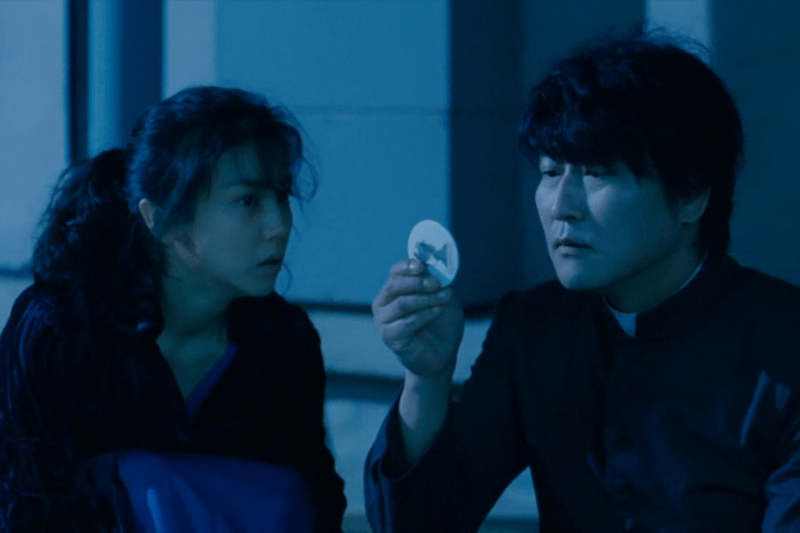

Thirst follows Father Sang-hyeon (Kang-Ho Song), a Catholic priest who provides end-of-life solace for hospice patients. The film is a surreal and often hilarious portrait of the impact of shame and the disparate power religion holds over its followers. Despite Sang-hyeon’s dedication to the cloth and those who look to him for guidance, it is apparent early on that he does not feel his humble service is enough to earn his place in heaven. The illusion of blind faith and the power of shame is a permeating theme throughout Thirst, with Sang-hyeon’s identity attached to his faith as if a prayer will fill the emptiness that he obviously feels within himself.

Desperate to find purpose in his ministry, Sang-hyeon volunteers his body for an experimental vaccination, allowing himself to be infected with a mysterious disease that seems to only sicken and kill single men. While being encouraged by the doctor to strongly consider whether his intention is one of martyrdom, Sang-hyeon insists his purpose is solely scientific. The viewer sees what the doctor doesn’t however, as Sang-hyeon prays that God will have him live in shame as his body rots and dies. His desire for such shame comes into play in later scenes showing Sang-hyeon self-flagellating as he fantasizes about his love interest, a woman he has known since childhood, Tae-Ju (Kim Ok-bin). Sang-hyeon so vehemently denies himself what he considers to be his baser nature, seeing it as a weakness that emboldens Satan, that the great struggle in the film is ultimately with himself.

A month after the initial experiment, Sang-hyeon suffers from unsightly and painful blisters, massive internal bleeding, and is given a blood transfusion before flat-lining on the researcher’s table. When Sang-hyeon comes back from the dead, much like the biblical Lazarus, he is quickly revered as a Saint by those in the Catholic church. While Sang-hyeon does not welcome the reverence, he also does not convincingly rebuke it. He has found the identity he was missing as a sacrificial lamb for God, resurrecting a more pious and devoted servant. Or so he believes.

The very instincts and impulses that Sang-hyeon worked his life to deny begin to awaken in him as he encounters Tae-ju. She is now married to her adoptive brother, Kang-woo (Shin Ha-kyun), and lives with Kang-woo’s mother, the overbearing and manic Lady Ra (Kim Hae-sook). Lady Ra showers Sang-hyeon with adoration, believing that he can save Kang-woo from the cancer that is killing him, and she invites the priest into her home as a frequent guest.

As Sang-hyeon immerses himself deeper into the family unit—interacting more frequently with Tae-ju—his memories become fantasies as shame causes Sang-hyeon to self-flagellate once more. His fantasies are fueled by the stirring of forbidden desires as well as the realization that his life has perhaps been dominated by a belief that he can neither enforce nor defend.

Tae-ju is drawn to Sang-hyeon; his child-like flirtations provide what she needs to open the door for Sang-hyeon’s first shame-filled sexual encounter. The scene is powerful, as both parties parry around one another—Tae-ju advancing, Sang-hyeon fumbling with an awkward kiss. The audible cues of wetness and slurping fill the soundscape, causing the viewer of Thirst to grapple with their own sense of anxiety over awkward sexuality. When Tae-ju removes her clothes, Sang-hyeon looks away, unable to allow himself to indulge in her body. Despite having just said that she doesn’t get shy, she covers her breasts and turns away, showing the impact that Sang-hyeon’s embarrassment has on her.

Despite his desire, Sang-hyeon holds fast to the belief that he is a sacred vessel of God. He cannot escape the overpowering resilience of the “values” instilled in him during his time in the church, and therefore cannot give himself over fully to either lust or love. For in reality, is there ever a more powerful weapon in organized religion’s holster than shame? As Tae-ju continues her advances toward him, pulling his pants down aggressively (with little consideration to his consent), he grabs a wooden ruler and whips his legs in a desperate attempt to lessen his arousal.

Then, in a beautiful and seemingly imperative moment, Tae-ju pulls his legs open and kisses the marks on his body, the scars from years of self-abuse, a tender declaration of understanding and acceptance. If she hadn’t persisted to show him that what he wanted was not a sin, but a perfectly human need, he may never have opened himself up to the experience of being with Tae-ju, body and soul.

They are interrupted before being able to fully carry out their act of passion but Sang-hyeon has found in Tae-ju a kindred spirit, one who has suffered but is unapologetic in her perceived solipsism. She gently teases him as he stresses that they will both go to Hell—she has no faith and doesn’t believe in Hell, so what risk is there to indulge in their desires?

Slowly, Sang-hyeon finds it harder to maintain his identity as a priest. As his skin burns in the sunlight and he is forced to extract blood from comatose patients in order to survive, it is not unreasonable that he questions his relationship with God, or even doubts the existence of God altogether.

Floodgates Open

In their first fully realized sexual encounter, the two exhibit a sense of deeply seeded desperation. Tae-ju writhes and wails, asking if she is a pervert after Sang-hyeon bites her, intensifying her craving. He kisses her feet, an image that conjures tales from the Bible, signifying that he has chosen his path and there is no returning to the man he once was.

Tae-ju becomes the altar upon which Sang-hyeon worships, replacing one compulsion for another. And though he still must face the fact that his sickness controls him, he has let Tae-ju in on his secret and has found a new purpose in his life: to save her from those in her life who wish to do her harm.

Sang-hyeon has regenerative powers and supernatural abilities as a result of his death and rebirth. But despite his universal ability to ease the suffering of others, he stays close to his comfort zone, and that comfort zone inevitably becomes Tae-ju. He doesn’t utilize his abilities to give everlasting life to even the most pious priest who he loves. And despite his stubborn refusal to accept his place as a savior—he understands the limitations of the sickness within his body—the concept of being a savior to Tae-ju is impossible to resist. He is finally able to realize the purpose he wished to fulfill within his congregation. He could finally save someone.

Unfortunately for Sang-hyeon, the last thing Tae-ju wants is for another man to control her, and she quickly begins to manipulate their relationship to satisfy her own needs. The devotional void left in the space Sang-hyeon previously kept for God and religion is quickly replaced by Tae-ju’s selfish desires. A part of those desires includes strong sexual fulfillment, and that temptation becomes far too strong to resist as Sang-hyeon finds the moral line blurring more and more as he and Tae-ju inch closer to hedonistic pleasure.

As the life of piety that Sang-hyeon had built his identity upon in Thirst unravels into a world of sex and horror, he is forced to come to terms with his choices as well as the implications of allowing a wild spirit like Tae-ju to become inflicted with his vampiric sickness. While he is able to control his thirst in a way that alleviates his guilt over leaving the church, he can’t control Tae-ju’s bloodlust or her refusal to play by his rules. The love he found outside of his faith was built upon Tae-ju’s lies and deception, and while the viewer does witness true affection from both at the start of the affair, it is impossible to deny the self-fulfilling prophecy that emerges when Sang-hyeon gives into his impulses.

Conclusion

Thirst is a brilliant look at faith and shame that manages to create new vampire lore. Park Chan-wook develops his characters frame by frame, peeling away their layers like dead swaths of skin. With each decision, Sang-hyeon and Tae-ju advance together based on the effects of their painful pasts. While Sang-hyeon is bound within the shadowy limitation of his shame, forcing himself to deny pleasure and feed only on the sick and dying, Tae-ju is desperate to break free from those who have denied her own identity and personhood.

Their love is violent, but ultimately is the only thing either can trust, and as the film careens toward a gorgeous climax, the viewer is uncertain who is really the villain, or if both parties are victims of unfortunate chance. It’s a bold move for Chan-wook to show his characters in this light, but Thirst benefits from the morally gray and nonjudgmental look at human nature.