Griffin Dunne’s Practical Magic is impractically tender and angelic (as far as genre representation goes), and I mean that as a compliment. It’s a film that centers around death and yet is a celebration of life. Characters nurture hope in the darkness, find meaning within the macabre, and reveal empowerment in individual representations of our honest, authentic selves.

Become a Free Member on Patreon to Receive Our Weekly Newsletter

For those unaware of the 90s charms this film conjures, Sandra Bullock and Nicole Kidman play the Owens sisters (Sally and Gillian, respectively). A terrible curse plagues all Owens women, accidentally enacted by a great-relative during colonial times. Whenever a man falls in love with an Owens lady, and marital bliss has taken hold, the male dies. From young ages, Sally and Gillian dream of finding their someday princes – but cruel fates will not allow for such happiness. Sally tries, which leaves her widowed and with two children, while Gillian pursues a life of sipping poolside tiki drinks and aggressively tanned boy-toys.

Then Jimmy Angelov (Goran Visnjic) enters Gillian’s life, subsequently exits after an abusive outburst, and reenters in the form of an evil apparition who haunts the Owens’ homestead because his corpse may or may not lay six-feet-under in their garden.

Thanks to classic 90s naivety, Practical Magic transforms what’s an observantly blackened tale (multiple men croak) into what’s cornier than Cupid’s favorite Hallmark special. As a hangman’s noose wraps around the oldest Owens’ neck, the score suggests moods akin to a pretty-in-pink tea party. As rituals are performed, the Owens sisters must improvise with household ingredients like when a pentagram is drawn using Reddi Wip from the refrigerator. Even the “sassier” scenes, when Gillian returns home and busts into PTA meetings on Sally’s timid behalf, are all so squeaky-clean and wholesome. It’s the kind of movie that favors togetherness over revenge, as enemies (mothers of children who chant “witch!” like bullies) come together in the name of ceremonial purification for a sweep-it-clean third act.

All that, plus a groovy midnight margarita dance sequence that hits out of nowhere, set to “Put The Lime In The Coconut?” Practical Magic is sweeter than cherry pie dipped in chocolate and topped with a mound of frosting (instead of whipped cream).

Of course, this is a movie about love. In its blissful, tragic, uncontrollable forms. How love heals us, damages us, and comes in customizable packages. Sally pursues her knight-in-shining-armor slice of suburban normalcy that many of us define as this Disneyfied version of perfection. Gillian would rather let her freak flag fly with European lothario types while cheesy porno background music plays. Aunt Frances (Stockard Channing) and Aunt Jet (Dianne Wiest) spend their lives together as companions who pass on their namesake supernatural trades, valuing domestic accompaniment. It’s this accountable one-size-doesn’t-fit-all approach that pushes against the very Lifetime Channel tone it skews, once again valuing a person’s unique gifts over conformity. Part parody, part love-letter to romantic variation. Like how I started saying “YOLO” ironically but then learned to love the admittedly-buffoonish phrase.

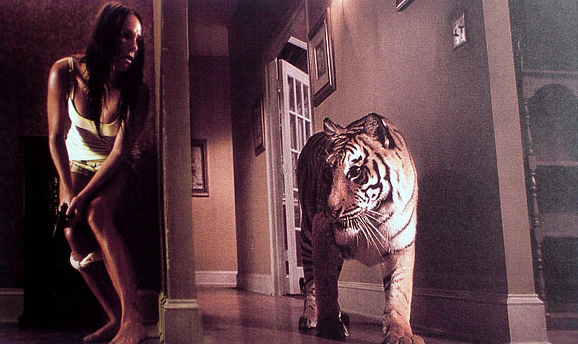

Practical Magic owes all its powers over audiences to Sandra Bullock and Nicole Kidman, whose chemistry on-screen is the true…hehe…magic. Two characters atoning for the “sins” of their ancestral past, driving down highways represented by hilariously inept green screen backdrops, serving sisterhood with this devotion you can’t help but cherish. Women getting back to basics, taking matters into their own hands, and seizing control of the lives they’ve let others dictate. Not to mention, Kidman gets to have some performative fun when Jimmy rises from the grave, out of his rose bush entanglement, and possesses Gillian. Kidman’s devious smirk within a circle of chanting housewives plays like she’s having a ball, still provoking sweaty intensity.

I’d imagine an exorcism would knock the wind out of anyone.

What can I say? I’m just a dude who’s a sucker for sisterhood flicks about broomsticks, levitation, and saccharine-sappy endings (it seems). Practical Magic is about eating chocolate cake for breakfast and defying convention as outsiders deem appropriate. About breaking the shackles of our heritage by embracing those very things we’d instinctually scramble to escape. It’s not the tone of film I’d immediately gravitate toward, but that’s the glory of being forced to watch something you’d otherwise stash for a rainy day. Consider this critic bewitched by a sunshiny-bright take on what could have been another overdramatic ode to lust and heartbreak gone too stern. Sincerity and silliness, instead, win with Halloween vibes to boot.

This witchy-whimsical romance was brought to me for July’s Patreon review request, by – how shocking – coven enthusiast and possible spellcaster herself (jury is still out), Amelia, who guested on the Patchwork episode of Certified Forgotten. Congratulations, you’ve earned yourself another Practical Magic convert.