Editorials

Reliving the Adolescent Trauma of ‘Sleepaway Camp’

Uterus Horror is a subgenre of films that focuses on the experience of growing up with a female gender expression. These films capture the act of becoming an adult and coming into your sexuality, using horror to emphasize and/or act as a metaphor for those experiences. Columnist Molly Henery, who named and defined the subgenre, tackles a new film each month and analyzes how it fits into this bloody new corner of horror.

July 15th, 2020 | By Molly Henery

Uterus Horror is a subgenre of horror films that focus on the unique experience of puberty and discovering sexuality as a woman, using horror elements to emphasize and/or act as a metaphor for that experience. Earlier this year, I began a column naming and defining the subgenre while also examining films under this umbrella. I previously discussed how Uterus Horror got its roots with Carrie and gained more recent popularity with the cult favorite Ginger Snaps.

Become a Free Member on Patreon to Receive Our Weekly Newsletter

While the films I previously mentioned focus more on the puberty side of the subgenre, now I want to dive into a different cult favorite that focuses more on the sexuality side of Uterus Horror: Sleepaway Camp. “But, Molly,” you ask, “Sleepaway Camp is about a character who is biologically male and therefore doesn’t have a uterus! How can this be Uterus Horror?” The important thing to remember is that while Angela was born male, by the time we meet her character, she is a young woman. It’s also important to remember that Angela’s experience is very much the same as any shy, quiet girl going to a crappy 80’s summer camp for the first time.

The main reason I named this subgenre Uterus Horror is to make men uncomfortable. Stories focused on young women and their physical and emotional changes are inherently uncomfortable for men to watch, partly because of the gorier physical aspects and partly because they historically aren’t told as much. These kinds of films about young men are typically called “coming of age” stories. For a long time, women were forced to see themselves in these stories because filmmakers weren’t making the same kinds of films about young women. Now that more Uterus Horror films are being made, it’s time for men to find themselves in women-led stories.

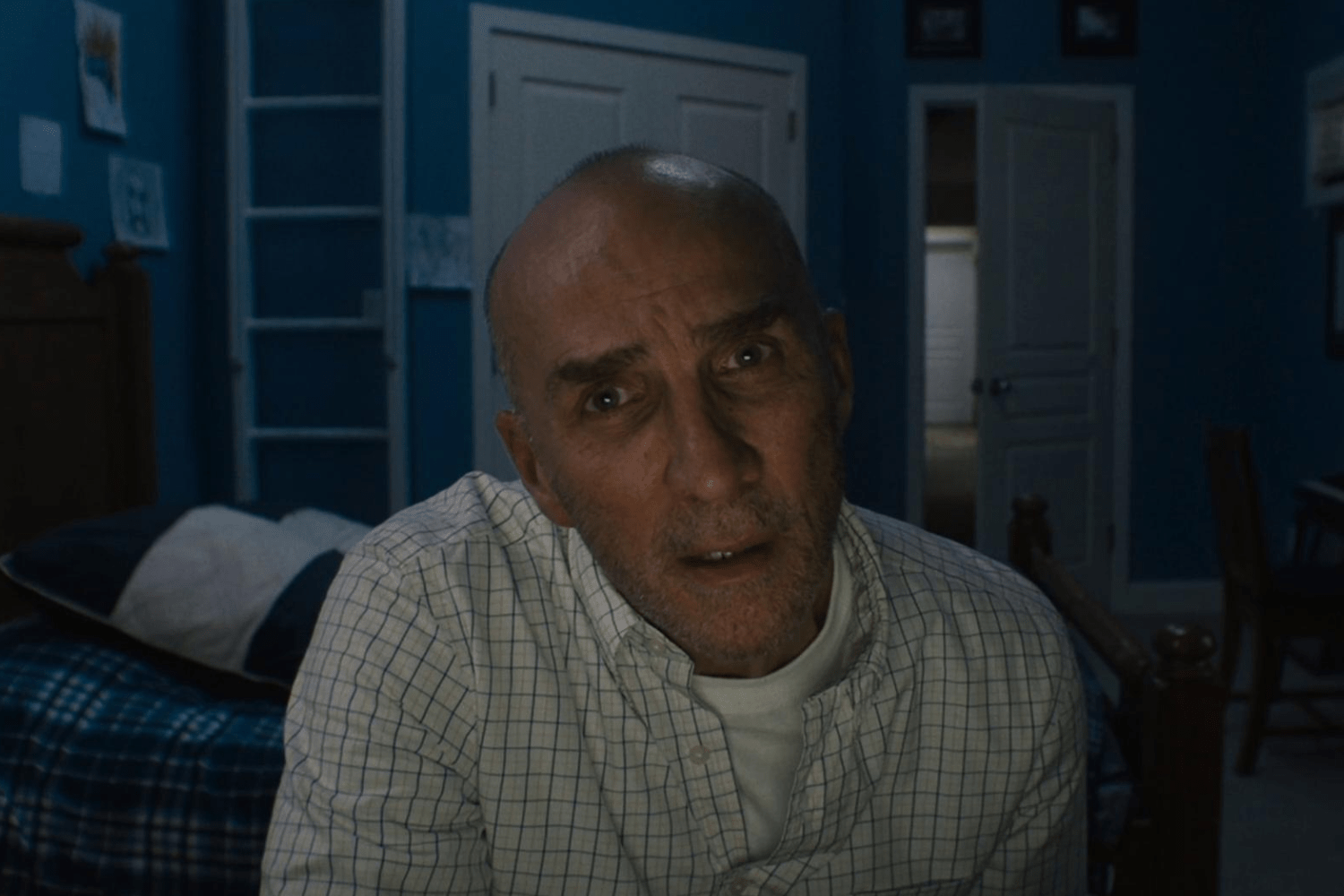

Sleepaway Camp is a controversial cult favorite horror movie by writer and director Robert Hiltzik. It opens with a family playing in a lake. As a father swims with his son and daughter, an out of control boat crashes into them, killing the father and one child. The sole survivor is sent to live with their clearly unstable Aunt Martha (Desiree Gould). Jump ahead eight years, and we see orphaned Angela (Felissa Rose) getting ready to go to Camp Arawak for the first time with cousin Ricky (Jonathan Tiersten). It’s obvious that Angela has been very sheltered up to this point in her life, but now she’s old enough to venture out into unknown territory. That also means she’s likely old enough to have begun puberty and start experiencing her own sexuality.

The moment Angela and Ricky arrive at Camp Arawak, the audience is introduced to some of the more unsavory characters. This includes the camp cook who refers to all the young girls as “fresh chicken” and “baldies.” Instead of being disgusted by what he says, the cook’s coworkers laugh it off and go about their day, because what would an 80’s summer camp movie be without creeps sexualizing underage girls? It also takes no time for Angela to become the target for two bullies, fellow camper Judy (Karen Fields) and camp counselor Meg (Katherine Kamhi). A normal part of the camp experience, made more terrifying by a serial killer’s presence.

There is an immediately apparent cause and effect with the murders occurring at Camp Arawak. Each person who dies previously wronged Angela in some way. The camp cook tries to sexually assault Angela, then gets a giant pot of boiling water poured on him. A boy at a camp gathering makes fun of Angela for being quiet, then he is drowned in the lake. Another boy hits Angela with a water balloon and later is killed when a beehive is dropped into the bathroom stall where he’s taking a “wicked dump.” In a final confrontation with Meg and Judy, Angela is thrown into the lake and then young campers kick sand at her. This embarrassment leads to rapid-fire murders as Meg is stabbed to death in the shower, Judy is killed with a curling iron, and even the young campers are found dead in their sleeping bags. We are consistently led to believe the killer is cousin Ricky based on how quickly and sometimes violently he defends his sheltered cousin Angela, but we all know that’s not the case.

The only people who are regularly kind to Angela are Ricky and Ricky’s friend Paul (Christopher Collet). Understandably, Angela develops a crush on Paul, leading to a summer camp relationship. Every girl who has ever been to summer camp has experienced getting a crush on a fellow camper and, if they’re lucky, having a seasonal fling with that individual. Unfortunately, summer camp heartbreak is just as common, which Angela also has to deal with when Paul is caught kissing Judy after Angela shied away from Paul’s physical advances.

The film’s now-iconic final moment shows Angela, naked, holding Paul’s severed head. The big twist ending is that Angela was not only the killer all along, but she was, in fact, born male. Her unstable aunt forced her to be a girl when the aunt took in the orphaned child. Based on the series of events, it seems likely that Angela finally wanted to show Paul who she was so she could be intimate with him. Paul, being young and a boy in the 80’s, likely did not respond kindly to learning Angela was born male, so Angela kills him to protect herself. Every single time she killed someone in this film, Angela killed to protect herself. The exception is Mel, the camp owner, who she killed because he beat Ricky until he was seemingly dead.

Angela’s story is always a point of contention with critics of the film, and it’s completely understandable. It can be looked at as if the filmmakers were trying to make a transgender character the villain, which isn’t a stretch since there is a long history of queer characters being portrayed as villains in film. With transgender individuals, there is an unfortunate cinematic stereotype that paints them as dangerous. Writer Harmony Colangelo wrote a fantastic article for Medium providing her opinion as a transgender woman regarding these harmful stereotypes and why she defends Angela’s character in Sleepaway Camp.

I’ve never watched this film and viewed Angela as the villain. Much like Carrie White, Angela is the victim of an emotionally abusive home life where she was sheltered from the outside world, combined with bullying and harassment by both peers and elders at summer camp. When the murders begin at Camp Arawak, Angela is merely protecting herself from those who are doing her harm. Also, despite being born male, Angela is a young woman. She may have been forced into that gender by her aunt, but it is clear at this point in her life that Angela identifies as a woman; therefore, she is a woman.

When we learn that Angela was born Peter and that she likely lived in a type of protective bubble maintained by Aunt Martha after the boat accident, the ensuing camp nightmare makes much more sense. Not only is Angela forced to fend for herself when she has never had to do that before, but she is also experiencing many things for the first time. She’s around a lot of other women for the first time and based on the way she stares at Judy that first day at camp, she notices that her body is different. Angela has been abused by family members in the past, but this is the first time her abuse comes at the hands of her peers. Even though Ricky does his best to protect her, Angela feels threatened by the bullies and does what she feels is necessary to defend herself. Obviously, Aunt Martha sheltered her so much that she never learned how to handle these situations the way most children do at an early age.

Angela is also getting attention from the opposite sex for the first time. From the camp cook, to the boys at the gathering, to Paul, Angela is having to get all of this attention while attempting to come to terms with her own sexuality. That is a lot for anyone to deal with, but Angela’s unique situation amplifies all of these thoughts and feelings in true Uterus Horror fashion. If it weren’t for Angela’s background and upbringing, these fairly typical camp experiences would have ended with tears in the bathroom stall and sad letters sent home rather than bloodshed.

It’s important to remember that Angela is the victim of Sleepaway Camp – not the monster – which means it’s time to stop treating her like a prepubescent Michael Myers. It’s also important to remember that, despite who Angela was at birth, her experiences of sexual harassment and first crushes at camp are things experienced by almost every young woman. If you take away Angela’s origin story and look at the events in the microcosm of her camp experience, it is the experience of every young woman. Sleepaway Camp proves that you don’t have to actually have a uterus in order for young women to experience Uterus Horror.