When My Best Friend is a Vampire first came out in 1987, it was just one of many teen monster movies that made up a very specific genre of horror comedies. It opened in less than 200 theaters across America, grossed just under $175k, and was promptly forgotten by audiences, even as films like Fright Night and Once Bitten developed their own cult followings. But while these other films serve as more well-known examples of how the teen vampire film explores burgeoning sexuality, My Best Friend is a Vampire not only examines the same themes, but expands upon them. It uses vampirism as a metaphor, however clumsily, for not just teen sexuality, but queer identity.

Jeremy Capello (a pre-Dead Poets Society Robert Sean Leonard) is every inch a typical teenage boy. He agonizes over girl problems with his seemingly more experienced best friend Ralph. He holds down a part-time job delivering orders for a local grocery store. Oh, and he also has a recurring dream about a girl from his high school that is continually interrupted by a mysterious older woman (Cecilia Peck). Normal boy stuff, right? But when he meets the woman from his dreams in real life and almost immediately begins an affair with her, everything changes.

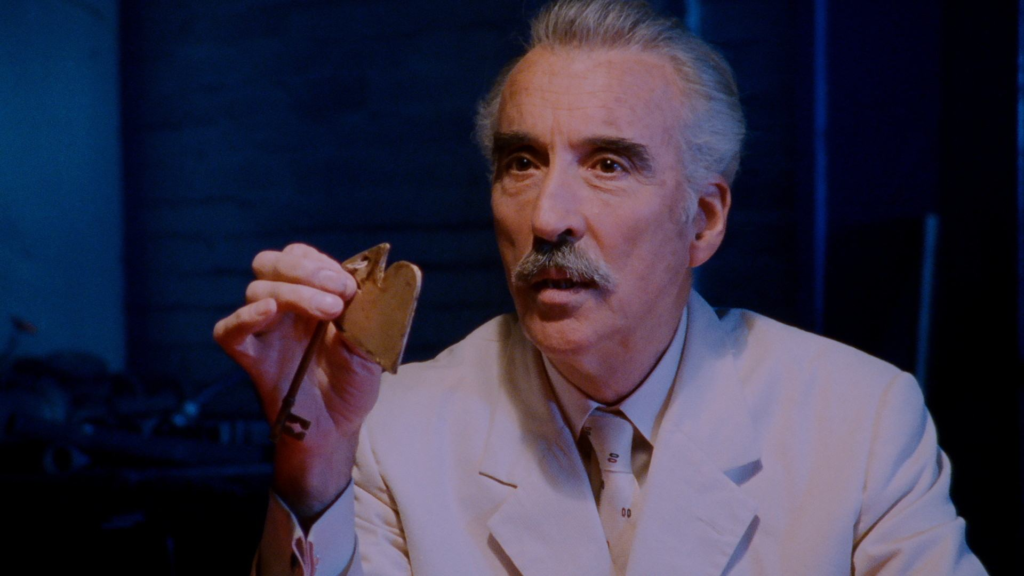

Jeremy tries to deny it at first, but the mounting evidence makes it impossible to ignore: Jeremy is turning into an honest-to-goodness creature of the night. It’s only with the aid of older, wiser vampiric mentor Modoc (Rene Auberjonois) that Jeremy begins to adapt to his new reality, and is able to fend off attacks from Professor Leopold McCarthy (David Warner), the most determined of vampire hunters.

From the very beginning of the film, Jeremy’s sexual anxiety is on full display. He has a dream that starts as a fantasy about two very attractive girls from his high school, and ends with him being castrated by a nun wielding a gigantic pair of gardening shears. You don’t have to be Freud to realize there’s something going on there, subconscious-wise.

Jeremy is deeply uncomfortable with himself as a sexual entity, and his inexperience makes him a target for Nora, the female vampire who seduces him. This is a repeated motif in vampire movies, especially those made in the 1980s which have a tendency to feature virgin (or, in the case of Jeremy, at least sexually inexperienced) teenage boys who are preyed upon for their innocence by alluring, dominant female vampires.

What we see here is a marked contrast to the way that women are often treated in horror films. The trope of the final girl usually entails a teenager surviving in part because she clings to her chastity as though it were a talisman capable of warding off evil. That’s one of the oldest mantras in horror cinema, isn’t it? “Virgins never die.” But interestingly, in these vampire films, the exact opposite seems to be true of teenage boys. Where virginity provides protection for their female counterparts, it’s essentially a liability for a teenage boy to be chaste — it actively puts him in danger.

It’s precisely because of his innocence that Nora is so easily able to lure Jeremy in, turning him into a vampire and setting in motion a chain of events that will see him in grave peril. His transition to vampirity, by contrast, presents fairly straightforward images of virility. His hunger for blood and raw meat reflect a desire for the flesh, and his newfound affinity for telepathy and mind control have overtly sexual connotations.

But My Best Friend is a Vampire goes beyond this concept of vampirism as a metaphor for budding sexuality. Instead, it uses Jeremy’s introduction to vampire society as a way to capture the experience of a teenager first encountering a distinctly LGBT subculture of the 1980s. When Modoc gently guides Jeremy through everything he needs to know about being a vampire, it’s with a kind and compassionate air. He wants to prevent a younger version of himself from being scared and confused as they attempt to mentally navigate a massive revelation about themselves. When Jeremy becomes overwhelmed by the implications of what being a vampire will really mean for his life, Modoc is quick to recount the positives of vampirism. And when Jeremy meets other vampires, they’re presented as a supportive community instead of a pack or coven.

Modoc doesn’t just help Jeremy come to terms with his identity, he teaches him the specific things he’ll need to know as part of a demographic that is very much under siege. The parallel is made abundantly clear as Modoc warns him of the vampire hunters and the danger they pose. Professor McCarthy and his bumbling henchman Grimsdyke (Paul Willson) have no clear motivation for why they’re so insistent on eradicating the vampire population. We aren’t treated to a backstory that could explain their all-consuming hatred, so an argument can be made that they hunt vampires simply because they don’t understand them. These hunters feel threatened by the way bloodsuckers live their lives.

My Best Friend is a Vampire is spectacularly unsubtle as it continues the vampirism-as-homosexuality metaphor in Jeremy’s relationship with his parents. It starts when Modoc appears at Jeremy’s house to give him some vampiric advice: his mother is convinced that she heard a man’s voice in his bedroom. The stranger Jeremy acts, the more his parents begin to suspect that their son is hiding the fact that he’s gay. Refreshingly, they are quick to accept this, and unreservedly support him.

But this is still the 80s, after all, and the film is unwilling to fully commit to the concept. Jeremy introduces Darla to them as his girlfriend, and they’re a little too pleased, in a “we loved you when we thought you were gay but we’re really happy now that we know you’re straight” kind of way.

My Best Friend is a Vampire is perhaps not as self-assured as other films from the same era that have gone on to richer and more popularized legacies, less committed to the ideas it presents. But it deserves some credit for dipping a tentative toe into subtext altogether different from what we were seeing at the time. It creates a vision of the vampire that is not just about sex and power, but unmistakably about identity, building a compassionate if occasionally bumbling throughline from the scared young man who has just realized he’s a vampire to the scared young man who has just realized he’s gay.

Visit our Editorials page for more articles like this. Ready to support more original horror criticism? Join the Certified Forgotten Patreon community today.