Editorials

‘Wicked’ Slyly Confronts the ’90s Erotic Thriller

September 15th, 2023 | By Tori Potenza

Nymphets, made famous in Nabokov’s controversial novel Lolita, were a focal point of 90s thrillers. Movies like The Crush, Poison Ivy, and Devil in the Flesh all turned girls into sex-crazed succubi. While second-wave feminism was in full swing, media portrayals of women were heightened in sexism. Allison Yarrow described this as the “bitchification” of women in a 2018 article in Time, with films often portraying liberated women as emasculators, whores, prudes, and nymphets. Yet one strange piece of media from 1998, Wicked, stands out from the others. It attempts to highlight psychological and societal factors that create these nymphets – and in doing so, ultimately subverts much of what made these movies so popular at the time.

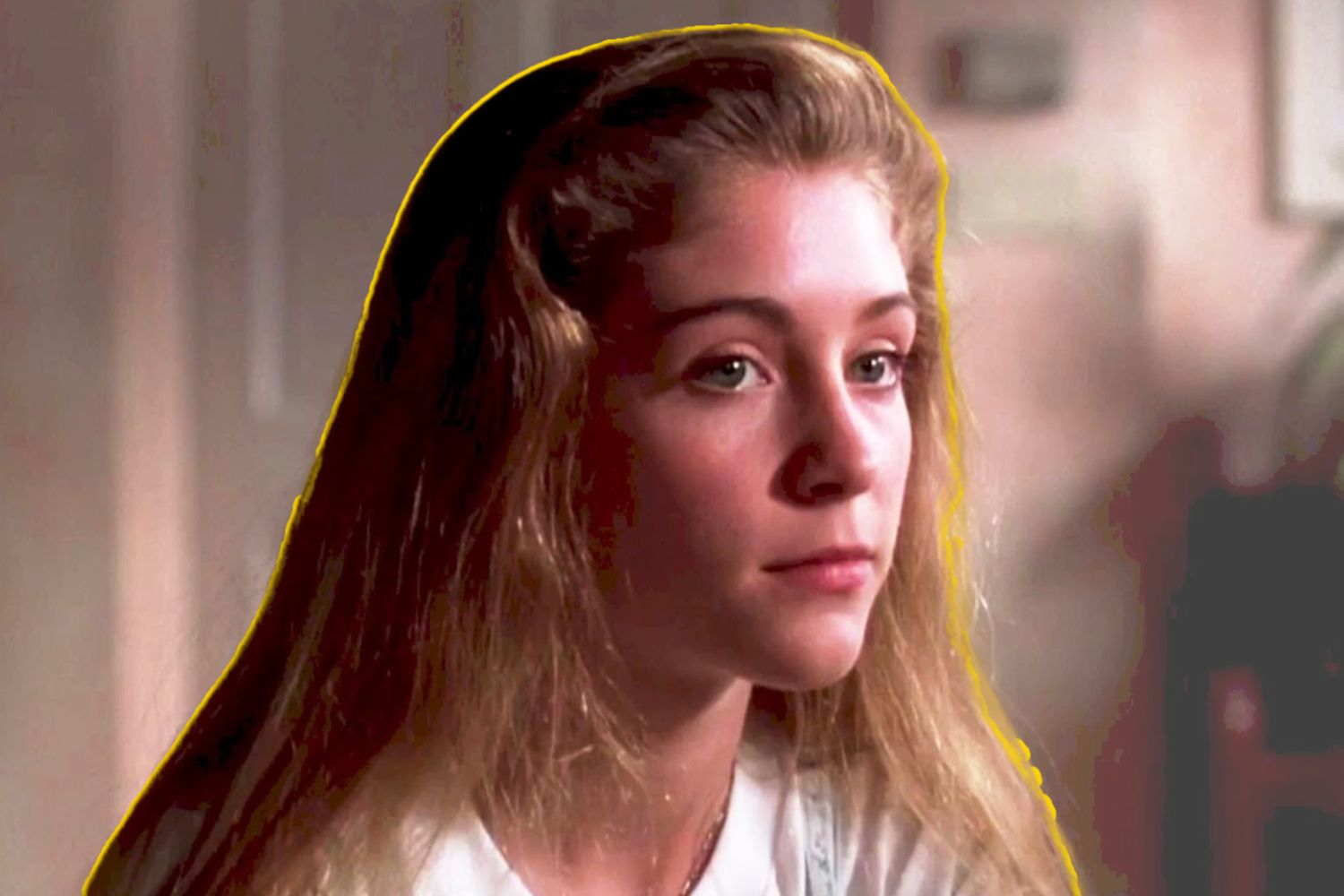

In Wicked, Ellie (Julia Stiles) portrays a 14-year-old whose personality mysteriously changes after her mother is murdered. The film had a festival run but could not find a home until it was released on VOD in 2001. Given the uncomfortable subject matter and strange tone, it is unsurprising that it struggled to secure distribution. Audiences had no qualms about watching depictions of overtly sexual girls, but director Michael Steinberg’s film does not revel in the sexuality of its lead, and the romantic elements are more taboo. It takes the fantasy away from its audience, which means it lacks beautifully shot sex scenes like Poison Ivy and doesn’t damn its lead like The Crush. Opportunities for carefree fantasy are limited in Wicked. Instead, its Lolita-esque story makes us confront the problematic subject material rampant in the 90s.

Wicked is hard to grapple with on an initial viewing. It has elements of a supernatural story and hints of possession or hauntings. This would certainly make it more palatable for viewers. The argument that Ellie is possessed by the ghost of her mother would help explain her sudden change in behavior, dress, and heightened sexuality. However, the less comfortable – but more plausible – explanation is that the movie lets Freudian/Jungian psychological theories move from theory to practice. Ellie’s change is because she is simply filling the psychological and societal role she is meant to fill in a home that has lost a maternal figure.

Carl Jung expanded Freud’s “The Oedipus Complex” to focus on women, dubbing it “The Electra Complex.” Young girls are attached to their mothers, but as they mature into puberty, they compete for the love of their fathers, seeing their mothers as competition. We often think it is “cute” when girls want to “marry dad” when they are young, but as they get older, they are meant to transfer this love to another man. We see this play out in the family dynamics of Wicked. Ellie is constantly at odds with her mother, but her younger sister Inger (Vanessa Zima) is devoted to their mother. The father, Ben (William R. Moses), dotes on Ellie and refers to her as his “favorite,” only fueling the competition of the women in the house.

Early on, Ben brings home a make-up kit as a gift to Ellie. She looks at the gift as a sign that her father sees her as a woman. Soon after, her mother is murdered, and this gives her the opportunity to become the woman of the house. While unspoken, it is expected that she takes on these duties, as Ben shows no interest in filling the void. Ellie must do whatever she can to keep Ben’s love. So she wears her mother’s seductive clothing and even sleeps in the same bed as him. It is only after Ben crosses the ultimate line with Ellie that he demonstrates any recognition of wrongdoing. Unable to understand what his daughters need, he brings his former lover Lena (Louise Myrback) and props her up as the new maternal figure. This only increases tension in the home.

Unlike other 90s lolitas – such as Drew Barrymore, Alicia Silverstone, or Alyssa Milano – Stiles is not portrayed as the seductive and sexy young girl. When she puts on makeup and dawns her mother’s outfits, we see a child playing dress up. While the men in the film sexualize her, the audience is not meant to. This takes away the fantasy because the movie constantly reminds us that she lacks maturity. This point is driven home even more so when looking at the changes Ingrid goes through in the backdrop of the film. As Ellie attempts to move into the role of mother and wife, Ingrid moves into the role of an angsty teenager. It is a cyclical story that continues to repeat, unbeknownst to any of the men in the film.

Unlike The Crush, it is harder to defend Ben. He is shown to be emotionally stunted and has no idea how to be a father. He can handle little girls but does not know how to act around a teenager and pushes her away like a disinterested lover. Things are complicated further when he assaults her. There is a layer of guilt, but his solution is to ignore the fact that it happened and push Ellie further away so she feels like she did something wrong. Ben knows only how to take from the women around him. He is neglectful, emotionally stunted, and unable to provide anything beyond surface-level love and attention.

The movie deprives audiences of the physical relations that Ellie and Ben share. When they go in for a kiss, the movie fades out and cuts back the following day with the two of them entangled on the couch. The acknowledgment that an assault happened does not occur until the end of the film after Ben has married Lena, and Ellie confronts him, saying, “I’ll tell her you have a mole on your left ass cheek, I’ll tell her everything.” She obtains power over him when she has completely given up on becoming his love and has now become the hardened and embittered woman her mother was.

This helps us see the real problems in these stories – these lolitas or nymphets are not adults, no matter how hard they try to be. Men can do all the mental gymnastics they want to justify these relationships, but they are still dealing with a child. One who, as we see in Wicked, is unable to differentiate between familial and romantic love. While much of psychoanalysis has been debunked, it does help us see how the expectation of traditional gender norms hurts us all. Wicked’s suburban location gives us visual queues as to the world these women grow up in and how it plays into their psychology and development. Trapped in the suburbs, they have little to look forward to besides the lives their mothers lead: caring for children and waiting for their husbands. Men leave for their day jobs, the only ones who can find an escape from the home. The outside world is only for them.

Ellie is teased by male classmates, who call her “Sasquatch.” After her transformation, one of these bullies notices her and says, “Looking good today, Sasquatch.” She smiles and blushes, ignoring the insult and focusing on the attention her new look brings. She begins to have some understanding of the patriarchal flirtation ritual. But only men like her father and her leary neighbor Lawson treat her like the woman she wants to be. Ellie is treated in varying degrees, with no real explanation as to why, so she simply becomes more confused and angry figuring out where she “fits.”

The movie’s dark ending reveals how, in patriarchal systems, women learn to destroy each other without men getting involved. They fight and claw their way to be the “favorite.” Women’s relationships are clouded in competition, and they struggle to have relationships not defined by men. Even adult women compete with girls. The passiveness of men shows how well they have rigged the system, they do not have to work for love or affection, while women and girls destroy themselves and kill each other over it.

While movies like The Crush, Devil in the Flesh, and Poison Ivy give us succubi and weaponize women’s sexuality to play into the “90s bitch stereotype,” Wicked stands apart. Ellie is still blamed for her own sexual urges, while her father’s transgressions are kept a secret. It diverts, however, by playing out a psychological fantasy that unveils societal ills. Unlike similar films, it refuses to exploit the sexuality of its lead, forcing audiences into the uncomfortable position of reflecting on their problematic fantasy. Wicked has much more going on than your run-of-the-mill erotic thriller and, ultimately, reveals the problems of gender norms, the patriarchy, and the 90s backlash against women.