Editorials

The Grotesque Perversion of ‘Visitor Q’

June 28th, 2022 | By Shae Sennett

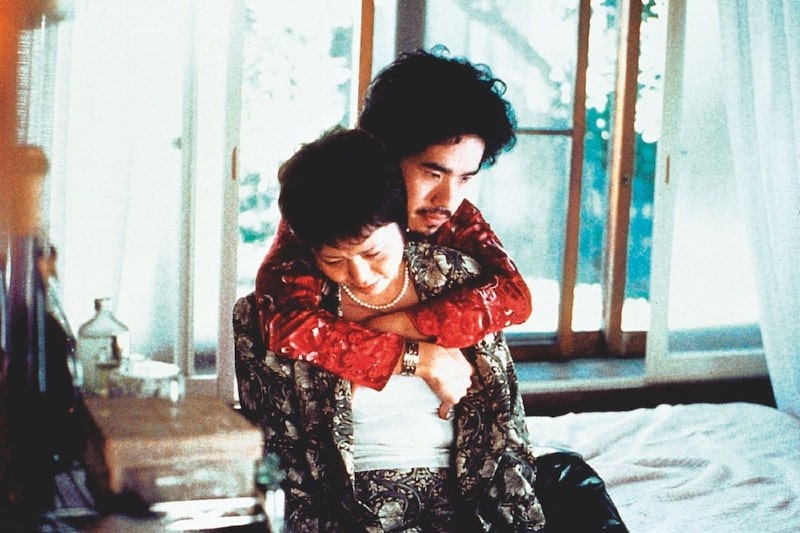

In Takashi Miike’s Visitor Q, the perverse and the grotesque become one. The film draws on the erotic tones of body horror, with its principles based on the penetration of bodily integrity. The body is both violated directly and metaphorically in the form of the family.

Become a Free Member on Patreon to Receive Our Weekly Newsletter

Like many films, this one begins when a stranger comes to town. The visitor introduces himself by bludgeoning a man on the head. Friendship is formed through a head wound, reversing the normal logic of pain and pleasure. He is an intrusive thought willed into being, the destructive conclusion of all subconscious inclinations willed into existence. He inevitably encourages each member of the family to give in to their darker impulses. Knowing that this visitor is violent, the father invites him into his home. The man celebrates the stranger’s penetration of his head and, later, his wife.

Rather than protect the family, the father encourages its destruction. He is a documentary filmmaker obsessed with the spectacle of his own violation. His career is ruined when he publicly broadcasts a clip of himself being sexually assaulted by a group of teenage boys. He discovers his son is being bullied and films it, making a spectacle of his suffering. His act of voyeurism seems to be an effort to reclaim his power, to penetrate the world with the eye of his camera rather than be penetrated. Instead, it only makes him seem more passive and pathetic.

The relationship between the bullies, father, and son comes to a climax when the bullies deploy fireworks into the family’s home, burning down the house. Once again, the father films it happening rather than intervening, questioning his emotions — “I don’t know how a father should feel,” he repeats. The house is a physical manifestation of the family, which is an extension of the body. Once the house is destroyed, the boundaries between the family and the outer world as well as their boundaries with each other begin to collapse.

Visitor Q heavily employs themes of abjection. In The Powers of Horror, Julia Kristeva defines abjection as the oppositional disgust which disturbs the integrity of the self. The foundation of this feeling is the child’s “primal repression” of their attachment to their mother. This detachment is achieved through forming barriers of separation between natural processes like vomit, feces, and corpses/death by learning how to feed and clean oneself.

In Visitor Q, the son violently enforces his abjection by beating his mother senselessly. She provides everything for her family — cooking, cleaning, and financially supporting them. Her son needs her and cannot take care of himself, so he lashes out. This relationship culminates in the mother’s uncontrollable lactation, which inevitably drowns her son.

Her husband and daughter experience an inverse relationship to abjection and become aroused by her lactation. In the end, they feed on her breast milk in an erotically charged scene of incestuous perversion. Sex leads to motherhood and breastfeeding, which is associated with the innocence of childhood. In Visitor Q, this order is reversed, and breastfeeding breeds eroticism.

As Kristeva suggests, the mother in this film is perpetually rejected and placed at the bottom of the symbolic order. Her body is deformed by beatings and a limp. The sanctity of her maternity is violated by her engagement in prostitution. This prostitution, though, is the only time she has any power. Her client is the only one that seems concerned for her and says she should go to the police for her lashings. He then pays her to whip him with a belt, pressing her to go harder. Just like the film’s other characters, his eroticism is tied up in violence and pain.

The father also inverts humanity’s natural aversion to dead bodies by having sex with a corpse. When rigor mortis occurs, his penis becomes trapped inside the body. The typical process of body horror is inverted. Instead of being penetrated by a foreign object that becomes incorporated into the body, like in Tetsuo: The Iron Man, the father penetrates a foreign body and is incorporated into it. Once again, the father attempts to dominate the Other and is instead rendered passive by it.

The relationship between the erotic and grotesque (or “ero” and “guro”) has been observed in Japanese modern society by sociologists like Yasuda Kiyoo, author of Erotic Film. Kiyoo says that “the border between ero and guro is one sheet of paper. Depending on the performer, the same physical actions can become entirely different in feel.” Miike seeks to parse out this paper-thin distinction in Visitor Q by bringing the extremes of arousal and disgust together in one film, one family, one act. Sexuality, typically compartmentalized from the family and the grotesque, is put in direct association with it. By eliminating this border, he inspires the viewer to define their own border more firmly — to protect the integrity of their sexuality from their subconscious impulses, or perhaps to prove that this will never be possible.

Miriam Silverberg, who authored Erotic Grotesque Nonsense: The Mass Culture of Japanese Modern Times, incorporates absurdity into this equation. The relationship between the erotic and grotesque can be found in the ridiculousness of comedy, which seeks to defy logic and order. Silverberg associates this humorous mentality towards sex and violence with the dissolution of social order in Japan. This violation of tightly organized Japanese social systems and the integrity of the national identity mirrors the violation of the body in body horror and the family in Visitor Q.

The erotic and the grotesque are met with an absurdity that Silverberg says is characteristic of Japanese modern society. Like Miike’s other films, his 2001 horror is tonally ironic and almost playful. The film’s extreme moments of sexuality and violence are excessively theatrical to the point of comedy. Even the tragic figure of the mother is made into a caricature by her limp and lactation. She, too, inevitably gives in to absurd perversion.

Miike finds an intersection between abjection and sex in the penetrative nature of body horror. An incestuous family’s boundaries are penetrated from the outside and within — their perversions are wedded with products of new life (breast milk) and new death (rigor mortis). Visitor Q finds the sharp comedic edge of humanity’s most horrific impulses and bludgeons us over the head with it.